Like his father, Alexander Carron Scrimgeour was a partner in J. & A. Scrimgeour, stockbrokers based in London. He used his considerable wealth to finance the National Socialist League and its founder, William Joyce.

Like his father, Alexander Carron Scrimgeour was a partner in J. & A. Scrimgeour, stockbrokers based in London. He used his considerable wealth to finance the National Socialist League and its founder, William Joyce.

Family background

Alexander Carron Scrimgeour was born on 27 November 1867 at Woodside in Jackson’s Lane, off Archway, Highgate in north London. He was the fifth child (of eight) and eldest son of Alexander Scrimgeour (1835–1882) and his wife, Anne Esther née Duguid (1832–1892). He was baptised at the family church, St. Michael’s in South Grove, Highgate, on 19 January 1868. Alexander Scrimgeour was a founding partner in J. & A. Scrimgeour, one of the leading firms of stockbrokers in London.

At the 1881 census, the family were living at 1 Queen’s Gate, Kensington (close to Kensington Gardens), with a governess, butler and 12 other staff. The younger Alexander (now 13), was recorded as a scholar.

Alexander was educated at Malvern College from where he matriculated in October 1886, going up to Christ Church, Oxford as a commoner. He graduated as Bachelor of Arts in the summer of 1891. At the April 1891 census, he was now living with his parents and family at “Wispers”, near Stedham in Sussex, when he was described as a student.

On his mother’s death on 14 January 1892, Alexander, aged 24, inherited the house at Wispers and property in the Manor of Stedham to the north of the River Rother, together with the riparian rights, plus cottages in the villages of Woolbeding, Stedham and Iping to the north of the River Rother.

Marriage and children

On 19 April 1892, at St Paul’s Church, Tottenham, Alexander married 24-year old Helen May Bird. She was the daughter of William Bird, an auctioneer, and his late wife Selina née Chaplyn (1841–1876). Following the death of her mother, Helen and her siblings were raised by her aunt and uncle, William and Sarah Chaplyn, who were farmers at Diss, Norfolk. Prior to the marriage, Helen had been a nurse probationer at the Tottenham Hospital (the Evangelical Protestant Deaconesses’ Institution and Training Hospital).

The couple had five children:

Alexander, born at Warwick Road, Paddington on 5 March 1897

Margaret, born in St. Pancras on 2 November 1901

James, born in Holborn on 8 June 1903

Anne, born at Tadworth, Surrey in November 1905

William, born at Tadworth, Surrey on 21 August 1909

At the 1901 census, the family were living at The Rectory, Wickhambreaux, Kent. Living with them were Alexander’s younger brother, John and his wife and daughter, plus a cook, a nurse and four other female servants.

The younger Alexander’s birth was not registered until February 1902, when his father’s address was recorded as “Bateman’s“, Burwash, Sussex. [See below]

Alexander was admitted to membership of the London Stock Exchange in November 1904, aged 36. On his membership application, he gave his home address as The Mill, Tadworth, Surrey.

The family were still living at Tadworth at the 1911 census, with a butler, groom, chef and three other servants. By March the following year, the family had returned to Wickhambreaux, at “Quaives”, where they were to remain until about 1926/27.

Bateman’s

On 13 April 1897, Alexander purchased a rundown Jacobean mansion near Burwash in (East) Sussex known as “Bateman’s” (previously known as “The Manor House”) together with part of nearby Dudwell Farm for £6,500. On the purchase contract, Alexander gave his address as 23 Warwick Road, Maida Vale.

In August 1898, he purchased the Park House watermill, followed in July 1900 by the purchase of Park Farm, both a few hundred yards to the south of Batemans, for £925 and £2,500 respectively.

On 28 July 1902, Alexander sold Bateman’s, plus the Dudwell Farm property and Park House mill (30 acres in all) to Rudyard Kipling, then of “The Elms”, Rottingdean for £9,300 (approximately £1.25 million in 2022 prices). Kipling had tried to buy the property two years earlier, but baulked at the then asking price of £10,000, so thought that he had secured a bargain, although the agricultural value of the land was minimal and the house was then inaccessible, down a very narrow, steep lane.

A month later, Alexander bought 10 fields (24 acres) north of Bateman’s for £1,000. On 21 February 1905, he sold this land to Kipling for £2,126; on the same day, he also sold Park Farm to Kipling for a further £5,000. Negotiations between Scrimgeour and Kipling had proved “tense” involving a fair amount of “haggling”, with Kipling referring to Scrimgeour as “wonky…he may swivel round at the last minute”.

First World War

Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, Alexander enlisted in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, serving on HMS President, a training ship moored on the River Thames, with the Anti-Aircraft Corps.

Alexander and Helen’s eldest son, Alexander, had joined the Royal Navy as a cadet in 1910, and during the war served as a midshipman, and later sub-lieutenant on board H.M.S. Invincible. He was killed on 31 May 1916, when the Invincible was sunk during the Battle of Jutland.

Further tragedy was to strike the family on 15 February 1919, when the younger daughter, Annie, died at Pigeon Hill, near Midhurst, where her aunt, Ethel, had established a Home for Delicate Children. The cause of death was recorded as whooping cough.

Politics

The family left Quaives in about 1927, after which they lived at various addresses in the Hampstead area, settling briefly at 1 Hampstead Square from 1929 to 1931. They then moved to Sussex, settling at Honer Farm, South Mundham, about three miles south of the road from Chichester to Bognor Regis, in about 1933/34.

By the mid-1930s, Alexander was heavily involved with the British fascist movement. His brother, John Alexander was married to Jessie Constance Greig, the sister of Sir Louis Leisler Greig, KBE, a former Scotland rugby international and Royal Marine, who was mentor to Albert, Duke of York (later King George VI). Greig was also a stockbroker and a partner in the family firm, A & S Scrimgeour, and was married to Phyllis Scrimgeour, a cousin of Alexander.

Louis Greig was an early member of the January Club, a discussion group founded in 1934 by Sir Oswald Mosley to attract support for the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Although it is not known if Alexander was a member of the January Club, Greig had soon introduced him to Mosley. Alexander was attracted to Mosley’s fascist views and quickly became a major financial backer of the BUF. It is alleged that he contributed at least £11,000 to party funds, bringing him to the attention of the Special Branch.

Alexander Scrimgeour is believed to have purchased 2,000 copies of “The Truth about the Slump”, published in 1931 by New Zealand neo-fascist writer A.N. Field, for distribution among as many “patriotic persons as he knew”.

In 1935, Alexander joined the newly-founded Anglo-German Fellowship. Originally created “To promote good fellowship between Great Britain and Germany and their respective peoples”, it soon became another quasi-fascist organisation dominated by anti-Semites, before disbanding at the start of the Second World War.

In March 1936, Alexander offered to fund a large BUF meeting at the Royal Albert Hall or Olympia, but stipulated that the meeting should be purely anti-Jewish in nature. He proposed that free copies of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” be distributed to the audience. Mosley felt that a meeting of this nature would be too inflammatory and could result in the end of the movement, so the offer was declined.

By November 1936, Alexander Scrimgeour and William Joyce, the BUF Director of Propaganda, had become close friends, each having a strong hatred of the Jews. Alexander wrote to Joyce that month:

Baldwin and his vile gang of corrupt paid pimps and ponces will hang themselves, only give them the rope.

We here at Honer are always delighted to see you, and all good and true Blackshirts, whenever you find it convenient to use this villa as a temporary rest house.

The Jews have fairly got Yankee land in their grip and so their bought man Baldwin speaking to order talks of Britain and USA coming together….what a stinking poxy leprous bugger the creature is.

By this time, the BUF was starting to lose members and becoming short of funds. Moseley sent Joyce to see Alexander Scrimgeour in January 1937, in an attempt to solicit a further donation, but by this time, Alexander had decided to leave the BUF and refused to support them financially any further.

Shortly after the meeting with Alexander Scrimgeour, William Joyce left his position with the BUF and was one of the founders of the National Socialist League. Alexander Scrimgeour immediately transferred his political affections to William Joyce and the NSL.

Alexander seemed to be firmly of the opinion that the Jews had engineered the abdication of Edward VIII in December 1936 and his replacement by his brother, Albert, Duke of York. On 29 January 1937, he wrote to Joyce:

I am really sorry but my views are such that I find it impossible to support Sir Oswald Mosley any longer.

I look upon the present occupier of the throne as a contemptible disloyal traitor unworthy of respect or loyalty, who deserves to be hanged. You must know that the Jews placed him on the throne.

Joyce hoped that he could use Alexander’s wealth so that he and the NSL could be serious rivals to Mosley and the BUF, but this was not to be.

In The Meaning of Treason (1949), Rebecca West refers to Alexander Carron Scrimgeour thus:

The City of London greatly respected a certain aged stockbroker, belonging to a solid Scottish family, who conducted a large business with the strictest probity and was known to his friends as a collector of silver and glass and a connoisseur of wine.

The old man’s last years were afflicted by a depressing illness, during which he formed a panic dread of Socialism, and for this reason he fell under the influence of Sir Oswald Mosely, to whom he gave a considerable amount of money and whose followers he often entertained.

The old man had a fondness for William Joyce, who, being a lively, wisecracking, practical-joking little creature, was able to cheer up an invalid.

Death

Alexander Carron Scrimgeour died at Honer Farm on 20 August 1937, aged 69. The cause of death was recorded as “Cerebral thrombosis, atheroma and myocardial degeneration“. The Helmsman (the NSL magazine) reported his death in its Autumn 1937 issue:

Alexander Carron Scrimgeour, great patriot, true gentleman, and unassuming scholar, died at Honer, Sussex on August 20th.

His funeral was held on 23 August at Golders Green Crematorium in north-west London. Apart from a few family members, the only recorded mourners were from the family stockbroking partnership. Although his two sons attended the funeral, his widow Helen was not in attendance, nor were any of his siblings. Despite their apparent friendship, William Joyce was also not in attendance.

His estate was valued for probate at £80,116 (equivalent to about £6 million in 2022). Alexander left nothing in his will to the National Socialist League, and Joyce became dependent on Alexander’s sister, Ethel, for further financial assistance.

Later family history

Helen May Scrimgeour survived her husband by eight years. In 1939, she was living with her son at West Street, Selsey, close to her sister-in-law, Ruth. Helen died at Pendean, in West Lavington, near Midhurst, on 5 May 1945, aged 77; the causes of death were “Cerebral thrombosis, atheroma of cerebral arteries, auricular fibrillation and myocardial degeneration”.

Ethel Scrimgeour helped finance Joyce until he left England and moved to Germany in August 1939, where he broadcast Nazi propaganda against the allied forces, earning him the nickname “Lord Haw-Haw“. During the Second World War, Ethel continued to correspond with Joyce, up to his execution for high treason in January 1946. Ethel died in Midhurst Cottage Hospital in January 1953.

Alexander Scrimgeour’s daughter, Margaret (known as “Peggy”), married Eric Francis Dashwood Strettell (1894–1970) in November 1922. In the First World War, he served with the Buffs (East Kent) Regiment, reaching the rank of Captain. He became a partner in the family stockbroking partnership in July 1932. During the Second World War, he enlisted again and joined the Pioneer Corps., retiring in September 1945 with the rank of Colonel, having been appointed OBE in November 1943. Peggy died in August 1981 and was buried alongside her late husband at Kirknewton, West Lothian.

James Scrimgeour followed his father into the family stockbroking firm, becoming senior partner in the 1950s. During World War II, he joined the Auxiliary Air Force, working in the Air Ministry from 1942, being appointed OBE, and retiring with the rank of Wing Commander. He was appointed CMG in June 1959 for “services to the Crown Agents”. He married widow Winifred Giles (1892–1984) in June 1928 and had two sons. He died in Bepton in August 1987, and is buried in Cocking churchyard.

William Scrimgeour served with the Intelligence Service during the Second World War, before being captured and imprisoned in the Netherlands. He retired with the rank of Captain in 1946. He died at Cocking Rectory in January 1986, and was buried in Cocking churchyard.

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk:

1871 England Census

1881 England Census

1891 England Census

1901 England Census

1911 England Census

British Phone Books, 1880–1984

England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858–1966

England, Oxford Men and Their Colleges, 1880–1892

London and Surrey, England, Marriage Bonds and Allegations, 1597–1921

London, England, Births and Baptisms, 1813–1906

London, England, Electoral Registers, 1832–1965

London, England, Stock Exchange Membership Applications, 1802–1924

Oxford University Alumni, 1500–1886

Surrey, England, Baptisms, 1813–1912

UK, City and County Directories, 1766–1946

UK, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Service Records Index, 1903–1922

West Sussex, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1936

Westminster, London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1935

Bolton, Kerry (January 2014) William Joyce. Counter-currents.com

East Sussex Record Office (The Keep):

AMS 5982. Records of the Batemans estate, Burwash

AMS 5982/1/24-35. The whole estate, 1886-1897

AMS 5982/1/36-50. Park House Watermill and other property acquired by Alexander Carron Scrimgeour

AMS 5982/1/51-55. Purchase of the Batemans Estate by Rudyard Kipling, 1902

AMS 5982/6. Dudwell Mill and Farm

AMS 5982/6/1-85. Dudwell Mill and Farm, purchased by Rudyard Kipling on 21 Feb 1905

AMS 5982/7/1-10. Land north of Batemans (24a 1r 12p), purchased by Rudyard Kipling on 21 Feb 1905

The Gentlewoman: 30 April 1892. Marriages: Scrimgeour–Bird

Hallam, Richard (editor) (2018). Scrimgeour’s Small Scribbling Diary 1914–1916. Conway. ISBN 978–1–844–86075–3

Holmes, Colin (2016). Searching for Lord Haw–Haw. Routledge. pp.66, 107, 120–122, 134, 368, 458. ISBN 978–1–138–88886–9.

Keeley, Thomas Norman (1995) Blackshirts Torn: Inside The British Union Of Fascists, 1932- 1940. Simon Fraser University

Laity, Paul (8 July 2004) “Uneasy Listening”. London Review of Books. Vol. 26. No. 13.

Lycett, Andrew (November 2015) Rudyard Kipling. Orion. ISBN 978–1–474–60299–0.

May, Robert (July 2019) Breaking Boundaries: British Fascism from a Transnational Perspective, 1923 to 1939. Sheffield Hallam University

Mourning the Ancient.com: William Joyce, The Truth

The National Archives: ADM 337/93/747. Scrimgeour, Alexander C Service Number: AA747 RNVR

Pugh, Peter Richard (January 2002) A Political Biography of Alexander Raven Thomson. University of Sheffield

thefamouspeople.com. William Joyce Biography – Facts, Childhood, Family Life & Achievements

Thurlow, Richard (1987) Fascism in Britain. A History. 1918–1985. I.B. Tauris Publishers. pp. 138, 143

The Times: 7 May 1945. Deaths: Helen May Scrimgeour

West, Rebecca (1949). The Meaning of Treason. Penguin. pp. 35 & 36.

West Sussex Gazette: 26 August 1937. The Late Mr. A.C. Scrimgeour

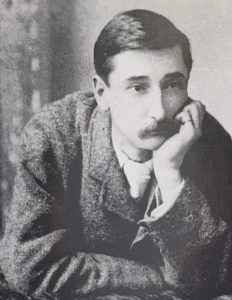

Photo credits

Portrait: Scrimgeour’s Small Scribbling Diary. 2008. Richard Hallam (Editor). Conway. ISBN: 978-1844860753. p.96