Regiment: 102nd Battalion, Canadian Infantry, CEF

Regiment: 102nd Battalion, Canadian Infantry, CEF

Service No: 911777

Date & place of birth: 25 October 1890 in Newington, Edinburgh

Date & place of death: 9 April 1917 (aged 26) at Vimy Ridge, France

David Hunter was the son of a minister in the Church of Scotland. He migrated to Canada, where he enlisted in 1916. He was killed on the first day of the Canadian assault on Vimy Ridge.

Family

David Ainslie Hunter was born on 25 October 1890 at 2 Mayfield Road in the Newington area of Edinburgh, the youngest of five children (all sons) born to Revd. James Hunter (1849–1915) and his first wife Clementina née Cowan (1860–1900).

James Hunter had been born in Airdrie in September 1849; his father, also James, was a commission agent, but later gave his employment as a quarry manager or colliery manager. On 14 August 1883, James, aged 33, married 23 year old Clementina Cowan, from Edinburgh, at Morningside Parish Church, Edinburgh. Clementina’s late father, George Cowan (1819–1881) had been a surgeon and a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons (Edinburgh).

James was the minister at Fala & Soutra, about 15 miles south-east of Edinburgh. The couple’s first son, also James, was born in November 1884, with four further sons being born over the next six years, with David being the last born, in October 1890.

Clementina died from influenza and pneumonia on 21 January 1900, leaving James a widower with five sons under 16. On 23 April 1901, at Aldershot parish church in Hampshire, James re-married, to Caroline Parry, a 45 year old spinster from Argyll, whose father Edward (1810–1884) had also been a doctor.

David and his brothers were educated at George Watson’s College, then situated in Archibald Place, just south of Edinburgh city centre. David was admitted to the school in 1897, and at the 1901 census, he and two elder brothers were boarding at 22 Elm Row, about 1½ miles across the city, with John Porteous, a travelling brush salesman, and his wife Catherine.

In August 1911, David, aged 20, left Glasgow on board the SS Hesperian, bound for Quebec, where he arrived on 13 August. The Hesperian was built in 1907 for the Allan Line, running a regular service across the North Atlantic. She could accommodate 210 passengers in first class, 250 in second class, and 1,000 in third class. In September 1915, she was sunk 85 miles south-west of Fastnet, following a torpedo attack, with the loss of 32 lives when a lifeboat capsized.

On arrival at Quebec in 1911, David gave his destination as Winnipeg, Manitoba and his occupation as “student”. By the time of his enlistment in 1916, he had moved further west and was living at 1120, West Pender Street, Vancouver, British Columbia and was working as a bookkeeper.

Masonic career

David Ainslie Hunter was initiated into Seaford Lodge No 2907 on 19 January 1917, alongside a fellow Canadian soldier, 50 year old Albert Robert Reeves. (Albert Reeves, a married man with three children, had been a regular soldier before the war, serving for 15 years with the East Surrey Regiment, before migrating to Canada. He survived the war, but died in Ontario in June 1933.)

David was sent to the front in February and was killed before he could make any further progress in Freemasonry.

Military service

Having served with the Canadian Army Service Corps before the war, David answered the call to arms at Vancouver on 28 March 1916, when he enlisted in ‘D’ Company of the 196th Battalion (Western Universities), CEF. The unit was initially based on the University of British Columbia campus with drilling, marching and arms training at the King Edward High School. On completion of recruitment, the unit joined the battalion at Camp Hughes in Manitoba, where they underwent further training in trench construction, trench warfare etc.

David was rapidly promoted, becoming a lance-corporal on 29 April 1916, corporal on 6 July and sergeant on 18 September 1916.

David was rapidly promoted, becoming a lance-corporal on 29 April 1916, corporal on 6 July and sergeant on 18 September 1916.

On 31 October 1916, the 196th Battalion sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia on board the SS Southland, bound for Liverpool, where they arrived on 11 November. The Southland was originally built in 1900 as the Vaderland, but was renamed in 1915 when she was requisitioned as a troopship. She was later torpedoed twice, firstly in September 1915, following which she was beached on Lemnos in the Aegean Sea, and repaired. In June 1917, she was again attacked and sunk off the Irish coast, with the loss of four lives.

On arrival in England, the 196th Battalion were sent to Seaford in Sussex where there was a large military base. Originally constructed shortly after the start of the war to house and train British troops, these were taken over by the Canadians in 1916. The base comprised two separate camps, North Camp (at East Blatchington) and South Camp (at Chyngton). Little physical evidence remains of the camps, the sites of which have been built over with the growth of Seaford.

At the start of January 1917, the 196th Battalion was absorbed into the 19th (Reserve) Battalion, with David being transferred to 102nd Battalion (Northern British Columbia), CEF (part of the 11th Infantry Brigade, 4th Canadian Division) on 12 February. He was shipped to Le Havre in France the following day, reaching his unit in billets at Hersin-Coupigny, 23 km north of Arras, on 21 February 1917.

The 102nd Battalion had arrived at the Western front in August 1916, initially serving in Flanders before moving to the Somme in October, taking part in the Battle of Ancre Heights. By the end of January 1917, after six months at the front, they had suffered 150 fatalities and were in need of reinforcements; David was part of a fresh draft of 60 “Westerners”, mostly from “University Battalions” recorded in the battalion’s war diary on 21 February, with a further draft of 53 men, described as “mostly from school” arriving on 5 March.

After ten days on “stand to”, on 2 March the battalion were ordered to march 16 km south to Berthonval Wood, just behind the front line. They spent the next ten days repairing and reinforcing the trenches; during this time, they occasionally came under artillery fire. The battalion war diary frequently mentions aerial fighting, “honours lying with the Hun”; “one little red machine of his was particularly noticeable and scored victory after victory”. This was almost certainly a reference to Manfred von Richthofen, known as “the Red Baron”, whose squadron was based at nearby Douai.

On 11 March, the battalion were relieved and marched 15 km north to billets at Bouvigny. The diary records: “This proved to be the most uncomfortable rest place provided since October 1916. The mud was intense and the huts crowded.” After a week of rest, on 19 March the battalion were again marched 9 km south to Villers-au-Bois, and then returned to Berthonval Wood.

The principal object of this ‘tour’ was the digging of a new front line trench and repairs to existing trenches, which were in poor condition because of mud. Once again, the battalion came under heavy artillery bombardment; Berthonval Wood lies about 3 km due west of Vimy Ridge, across the shallow Zouave Valley. The diary again reports “aeroplanes very active all day. German red machine very fast and successful in swooping attacks”.

The battalion remained in the area preparing for the anticipated assault on Vimy Ridge, alternating with spells in the trenches at Berthonval Wood or in reserve at St. Lawrence Camp at Chateau de la Haie, near Carency.

The first week of April was spent in training with the troops practicing “going over in waves, wearing the full equipment which they would be carrying on the day itself”, with the training often being interrupted by heavy snowstorms and strong winds.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge

Vimy Ridge runs for approximately 7 km north of Arras, at an elevation of up to 145 m, some 60 m above the Douai Plains, thus providing an unobstructed view in all directions, especially over Lens and its surrounding coalfields. The Germans had taken control of the ridge early in the war and had held it against several attempts by French and British forces to regain control of it.

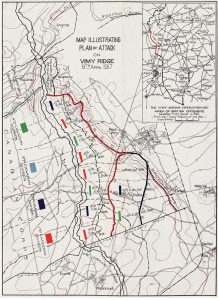

In late 1916, the Allies started planning for a major offensive in the Arras region hoping to break through the German defences and seize control of the ridge and the plain below. The plan was for the four divisions of the Canadian army to fight together for the first time, to take the ridge while other British units would push forward to the south.

The Canadians spent the winter of 1916-17 preparing for the battle. It was the worst European winter in 21 years; cold and wet, freezing rivers solid. By the time of the planned assault, every soldier, both in the ranks and officers, knew what he had to do and when he had to do it.

On 8 April (Easter Sunday), the 102nd Battalion moved into position for the operation, which started at 5:30 the next morning in a snow and sleet storm. The unit was on the right flank of the 4th Canadian Division and their primary objective was Hill 145 (named after its height in metres), the highest and most important feature of the whole ridge. To the north of Hill 145 (overlooking the town of Givenchy-en-Gohelle) was a small knoll, known in 1917 as Hill 120 or “the Pimple” to the Canadian soldiers. This was the location of German machine gun posts, the fire from which inflicted heavy casualties on the advancing Canadian infantry.

The Canadians took control of most of the ridge on the first day of the battle, with The Pimple being secured on 12 April, but with heavy losses, the allied forces suffering over 10,000 casualties in the battle, with 3,600 being killed.

Death and commemoration

The war diary of the 102nd Battalion reports casualties of the battle, mostly on the first day, as:

Officers – Killed 4, died of wounds 2, wounded 9

Other ranks – Killed 113, died of wounds 6, missing 27, wounded 180.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission reports 127 deaths from the battalion in the three days of the battle, including Sergeant David Hunter and the six officers.

David Hunter’s service file records his death thus:

Killed in Action – while taking part with his battalion in a successful attack on the enemy’s position at Vimy, he was killed by enemy machine gun fire.

He was buried at Givenchy Road Canadian Cemetery, which is situated in the compound of the Vimy Memorial Park which contains the Vimy Memorial. His grave bears the inscription: “If we suffer, we shall also reign with him”. (2nd Epistle to Timothy, Ch.2, v.12)

David Ainslie Hunter is commemorated on the war memorial at George Watson’s College, Edinburgh.

Other family members and subsequent history

David’s father, Revd. James Hunter died, aged 66, at Fala Manse on 26 November 1915 from acute bronchitis and lobar pneumonia. Caroline then went to live with her brother, Revd. Malcolm Parry at Astley Vicarage near Shrewsbury. Having resumed her maiden name, she died, aged 76, on 8 September 1926 in Southbourne on Sea, at the home of her cousin, Ethel Parry Rees, and husband, Revd. John Francis Rees, whose son, Lieut. Kenneth Rees had been wounded at Menin Road, near Ypres, and died at Calais on 29 August 1917 age 22, while serving with the Cheshire Regiment.

David’s brothers, William Henry Gray Hunter, and Charles Cook Hunter both migrated to Australia. William served in the war with the Australian Army Medical Corps. He survived the war and died in New South Wales in 1954, aged 67.

Charles served with the 2nd Divisional Ammunition Column and fought at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. He was invalided out of the army in October 1916 with influenza and returned to Scotland, where he died on 21 November 1919 from pulmonary tuberculosis.

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk

1891 Scotland Census

1901 Scotland Census

England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966

United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Records, 1751–1921

Ancestry.com

Australia, WWI Service Records, 1914-1920

Canada, War Graves Registers (Circumstances of Casualty), 1914-1948

Canada, Soldiers of the First World War, 1914-1918

Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865-1935

Statutory registers: Births

Statutory registers: Deaths

Statutory registers: Marriages

Canadian Great War Project: Sergeant David Ainslie Hunter

Canadian Soldiers.com: Vimy, 1917

CWGC Casualty Details: Hunter, David Ainslie

English Heritage: Kitchener’s Camps at Seaford

Find a Grave: Sgt David Ainslie Hunter

Gould, Leonard McLeod, The Story of the 102nd Canadian Infantry Battalion, Chapter 5

Library and Archives Canada:

War diaries – 102nd Canadian Infantry Battalion

Masonic Roll of Honour: Sergeant David Ainslie Hunter

Midlothian Roll of Honour 1914 – 1918

Military History Society of Manitoba: Camp Hughes

Veteran Affairs Canada:

Canadian Virtual War Memorial: David Ainslie Hunter

Western Universities Battalion, “D” Company, 196th Battalion

Wikipedia:

196th Battalion (Western Universities), CEF

Photograph credits

Gravestone: Canadian Virtual War Memorial: David Ainslie Hunter

2 Mayfield Road, Newington, Edinburgh: www.edinburghprimeproperty.com

The Parish Church of Fala & Soutra: http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/225645 (© Copyright Bill Henderson and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence)

Camp Hughes: Town of Carberry: Camp Hughes

Trench map: Wikimedia Commons: Plan of Attack Vimy Ridge Drawn by the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, printed by Geographical Section, General Staff, Department of National Defence

George Watson’s College War Memorial: The Scottish Military Research Group – Commemorations Project