Previous chapter: Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery

September to October 1942

Where are we now? Getting into the end of September I suppose. The raid on Tobruk was over and the battle hadn’t begun and eventually we were told it was on. The night of 24th October. At 9.40pm there was going to be a barrage of guns and our unit was expected to send the sappers through to open up minefields and of course there were infantry, tanks, everything. Again we drivers were more or less redundant at this point because they didn’t need a lot of vehicles and there was no point in driving vehicles around just for fun so apart from moving up from one position to another, when we were told to, and staying there, we didn’t do very much.

The desert was all marked out in tracks with little posts at the side of the road with either a cut out star or a crescent moon or a round one representing the sun. The different things that was all easily recognisable to all these different armies and languages. I think we were on the ‘star’ track. We were told to follow a ‘star’ track so far to such and such a landmark, like three forty gallon barrels, or something like that. This was the way they got everybody into position on what was more or less a featureless bit of desert. We sat there in the truck.

The first time we had ever known that anything was going to start happening, sat there in the truck looking at the watch until it got to be ‘twenty to ten’ and then sure enough all hell opened up. The whole skyline seemed to flicker and light up with the gunfire, the flashes of the guns, and the noise was absolutely incredible. It was impossible to talk to anyone even at a foot distance. There was a tremendous accumulation of noise from all these guns. The ones that were nearest of course being the worst for your eardrums, but everybody else filling up the gaps. It just went on for hour after hour after hour and eventually for day after day, not on quite the same intensive scale but continuous gunfire for several days.

We happened to be stuck near a battery of five point five Howitzers, quite big guns and they were towed by an AEC tractor; a big four-wheel drive thing called a Matador, and a fairly sizeable crew. The shells were pretty hefty things, as much as a man could stagger along with and the boxes of shells were piled up all around in great stacks where they had been unloaded off lorries. I, with nothing to do at all, no duties, decided the only thing to do was lay down and go to sleep, as it was the middle of the night. I got down between two of the stacks of shells, working on the principle that if somebody dropped something I was more likely to be killed by blast or shrapnel than I was by the actual shells being hit and exploding.

Then we had a fireworks display as the Luftwaffe came over dropping flares to try and identify something to drop their bombs onto. It must be extremely difficult at night dropping flares, to actually see what’s down below you to make any sense of it, because apart from dropping bombs all over the shop they didn’t seem to worry anybody too much and it was very rare for anything to get hit.

This kind of thing went on for several days and eventually after what you might call hard slogging and a lot of our chaps getting lost in these minefields, they were going to make the breakthrough with armour. Then the trucks came into use because we were moving people forward. I was at that time a corporal and didn’t have a truck. I was just in charge of so many drivers and so many trucks so I had nothing to drive and after a while I felt a bit guilty sitting around while these chaps were going out night after night, driving through these mine fields and things. So I said to Eric Frear “Give yourself a break and I will take your truck tonight” and off I went on what ever we were going to do.

It turned out what we were going to do was lead an Armoured Brigade, the 23rd Armoured, through some mine fields and hoping that they could come out into the open on the other side and then start getting down to business. Well, I was loaded with our section of sappers and it was dark and waiting for the moon. Eventually the moon came up and lighted things up a little bit and we were driving through the tapes in a minefield, the marker tapes to show you where the minefield had been cleared and this was done with white ribbons and in places little cycle lamps with a tiny pin hole of light in the cardboard cover over them. They were pointing back to us and couldn’t be seen from up front of course. We got to a certain point when enemy shells started bursting around us and the truck was roaring away in low gear pulling through this softish sand. You couldn’t hear anything arriving. You only saw the shell bursts and the red-hot shrapnel flying around in the dark, which was quite spectacular.

I realised after a while that there wasn’t anybody else in the truck at all except me and they were all walking along on the leeward side of the truck taking cover from it. So I thought, it’s all right for you lot! Anyway we drove on and then came to an area where the truck went down into deep holes and clambered its way out again. I couldn’t see where the hell we were going. I just kept driving between these tapes. It turned out afterwards that what we had been driving through was the German forward slit trenches which they had abandoned and the old truck was nobly ploughing through these trenches, clambering out again, making full use of its four wheel drive of course. We carried on like this for quite a long time, I don’t know the distance either, it was impossible to tell and everything was flying around when it started to get daylight and we pulled up and you could see across a valley, a very shallow valley, but about a mile across.

Over on the horizon there were hundreds of little twinkly fires and it must have been the Germans cooking their breakfasts if you can believe it. Right behind us was this load of tanks, Crusaders. They opened up. We were slightly down slope from them so they were firing over our heads. The blast of their shells was so low, so close to us that you could feel your tin hat lifting and dropping back on your head again every time one of them went over, which after a while you took no notice of but at first it was literally hair raising These shells were bursting over on the horizon. Most of the fires promptly went out and then of course it began to get more daylight and we trundled off again and we were out of the minefield then. There were no tapes. We were driving along, behind me were Daimler armoured cars and then behind that these two Crusader tanks.

All of a sudden there was one hell of a wallop and the truck flew up in the air. Everything went black and I knew I had hit a mine and thought I had lost my sight, blinded, because it was total blackness. It was simply the smoke from this mine. It drifted away and I could see again and thought “thank God for that.” It was one of our mines fortunately, not a German mine, otherwise it would have blown the front off the truck. In true British Army style our mines were about a third of the explosive quality of the ones the Germans were using. If you were going to hit a mine it was better to hit one of ours. It blew the front wheel off the truck and the metal floorboards up in a big bow under’ my feet. Rolling about on the floor were quite a few hand grenades and those flash grenades, which we were issued with. These had jumped out of their containers and were rolling about all over the floor. Lucky they didn’t seem to mind being blown up. They didn’t explode or anything. I got out to see what damage had been done and realised the truck wasn’t going to go much further.

At that point one of these Daimler cars, they call them Dingoes, came cruising past about fifteen feet away and he hit a mine. They had all been laughing their heads off in this Dingo at our plight when they hit one as well, promptly blew me over and Captain Wilson who had just arrived to see what the heck was going on, it blew him flat. We both got up again and another of these Dingoes went out round the first one and damn me he hit a mine as well. So that we must have blundered on to the edge of an old British mine field which hadn’t been marked or the markings had been taken away.

Then the tanks arrived. They were crunching there way through, trying to climb over the front of my truck because they knew I had hit a mine and if I had hit one already they knew there probably wasn’t going to be another one nearby. They were jamming their tank between my truck and this disabled armoured car and I said foolishly the kind of thing you would say, I suppose, under the moment. I said to Captain Wilson “Look what they are doing to my truck”, because they were climbing and tearing the front wing off it. He, just as stupid as me, rapped with his cane on the side of the turret of this tank. The tank commander’s head came out and Captain Wilson said, “Keep away from our truck”. The chap said “bollocks”, slammed the lid down and drove on. Which you could hardly blame him for but it was funny.

Anyway, when it all died down Captain Wilson said, “You had better walk back, Earley. There is nothing you can do here”. So I got my rifle and haversack and trudged back down the way we had come. It was the most peculiar feeling there was; hardly anyone about. Everybody had gone on. There were slit trenches here and there.

When I had got back half a mile away I came across an Australian soldier standing in one of these slit trenches and he said “Hi ya cobber, want some breakfast”, I said “what have you got then”, he said “I’ve got some bread and I’ve got some butter ‘ere”. I thought, “I haven’t had bread for months, and butter since the war started,” so I left my rifle up on the top of the trench and dropped down in. He had a lovely hole cut out. He had cut a hole in the wall of the sandy trench he had dug and kept his food in there where it was like a little fridge, it kept it cooler. So he produced this loaf, slapped butter out of a tin all over it, sliced it off and handed it to me and did the same for himself and we stood there munching this bread.

I said, “What the hell are you doing here”. He said, “Well we are the front line.” I didn’t like to tell him that the front line had moved on so I said, “Oh, I didn’t know that.” “Yes,” he said, and just at that moment an Australian officer came running along. There was no other slit trench visible. They must have been stretched out along somewhere, and he said, “Prepare to be attacked at any moment.” I thought, “Oh bloody hell, this is no place for a parson’s son!” I got my rifle, loaded it, and stuffed it on the parapet again. The Aussie did the same and we sat there sort of tensely waiting for this attack that was going to happen any minute. Nothing happened at all. I don’t know whether this bloke was deolali or whether he had got false information or what the heck it was but we didn’t see or hear anything happening of any particular note, so after a while I unloaded my rifle and said, “Right, I’m off. Thanks for the breakfast.” I hopped out and continued trudging back to our own line.

The desert all round me was pretty empty of life as far one could see. It certainly wasn’t empty of noise and turmoil because during all of the time, the artillery was firing in one direction or the other. The Jerries were firing airbursts from an Eighty-eight millimetre somewhere, which came uncomfortably close. These were fired so that they exploded in the air above you and if you happened to be underneath one when it went off bang, it not only gave you a fright but you stood a very good chance of being hit by bits of shrapnel that were hurled down from the explosion. I remember squatting to relieve a call of nature when one of these burst right overhead. My first thought was for the security of bits of me which were not usually on display and secondly that they must have good binoculars to notice me!

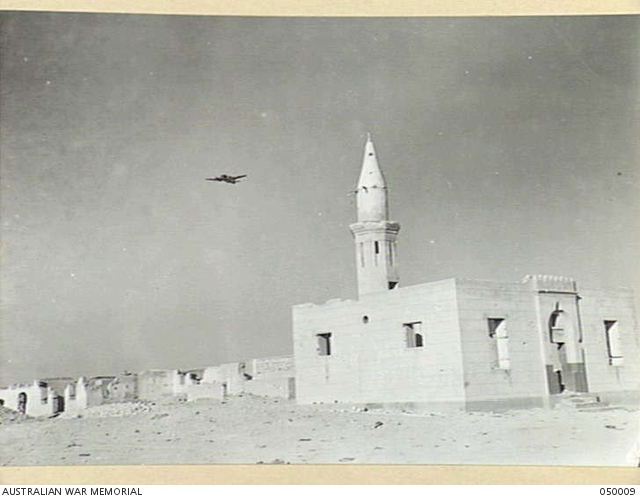

The prominent feature on the skyline to the westward was a tall minaret belonging to a mosque that was the only spot on the map. The name, I can well remember now. It was after the saint who was supposed to be buried there, one Sidi Abdel Rahman and the Germans were reputed to use this as an observation post for their artillery. There were constant attempts to knock this mosque, to hit this minaret with our own shellfire, but so far no one had managed to do it.

It was around this time that our CO was killed, Major Baker-Cresswell. He had joined us in Cyprus and was instrumental in making us into a much better unit than we were before and we were very upset to hear that he was killed. It happened when one night again he was doing a reconnaissance around the front of the area where we were working. He had an armoured car and the Germans hit it with a shell, I presume they must have had direct line of sight with an anti-tank gun or something. The armoured car was knocked out and he was killed along with his driver. We were left again back to Captain Wilson to be our acting CO until they provided us with another Commanding Officer. This was the second time that this had happened to us of course.

Note

Major Gilfrid Edward Baker Cresswell was killed on 27 October 1942, aged 27. He was buried at El Alamein War Cemetery. The driver who was killed was probably 37-year old Sapper Thomas Hitchen, who was the only member of 295 Field Company who was killed that day.