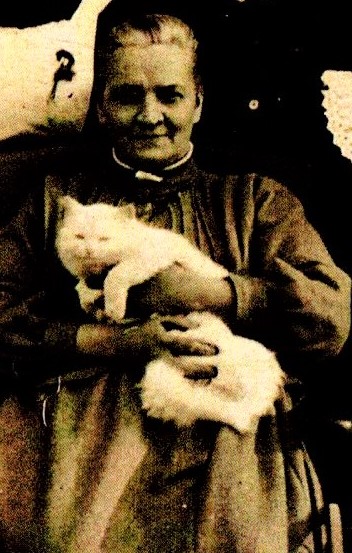

Born into a family of wealthy stockbrokers, Ethel Scrimgeour had set up an orphanage in Stedham before she trained as a nurse. In 1904, she established a Home for Delicate Children at Pigeon Hill, near Woolbeding, Sussex, where she nursed children with tuberculosis. Towards the end of her life, she was friend and financier for William Joyce, later known as “Lord Haw-Haw”.

Born into a family of wealthy stockbrokers, Ethel Scrimgeour had set up an orphanage in Stedham before she trained as a nurse. In 1904, she established a Home for Delicate Children at Pigeon Hill, near Woolbeding, Sussex, where she nursed children with tuberculosis. Towards the end of her life, she was friend and financier for William Joyce, later known as “Lord Haw-Haw”.

Family background

Ethel Scrimgeour was born on 6 March 1865 at Woodside in Jackson’s Lane, off Archway, Highgate in north London. She was the third daughter of eight children born to Alexander Scrimgeour (1835–1882) and his wife, Anne Esther née Duguid (1832–1892). She was baptised at the family church, St. Michael’s in South Grove, Highgate, on 10 April 1865. Alexander Scrimgeour was a founding partner in J. & A. Scrimgeour, one of the leading firms of stockbrokers in London.

At the 1881 census, the family were living at 1 Queen’s Gate, Kensington (close to Kensington Gardens), with a governess, butler and 12 other staff. Ethel, aged 16, was recorded as a scholar.

Ethel’s father had built their new Sussex home, Wispers, near Stedham in 1874/76; after his death in February 1882, Ethel’s mother moved to Wispers where she was living with six of her children in 1891, including 26-year old Ethel. Resident in the house were a cook and eight other servants. The butler and groom, and their families were living in separate cottages in the grounds.

Myrtle Cottage Orphanage

By 1901, Ethel had established an orphanage at Myrtle Cottage in Stedham village. That year’s census recorded ten children living at the orphanage, with a matron, 30-year old Annie Cawker, and an assistant and a laundress. The children, seven boys and three girls, ranged in age from 2 to 14, including Alfred Cook from London, described as a “cripple from birth”.

In 1911, the orphanage was now under the control of 43-year old Harriet Winmill, with an assistant and ten children (four girls and six boys), each described as “protégé”, including 12-year olds George Cherry and Timothy Macarthy and 14-year old William Francombe all of whom were living at the orphanage ten years earlier.

The matron at the orphanage at Myrtle Cottage at the 1921 census was 47-year old Amelia Hankins, with one 15-year old servant, Dorothy James, and 11 children (six boys and five girls), including three sisters, Phyllis, Winnie and Violet Perry (11, 9 and 7) from Leicester, and two brothers, John and James Walsh (9 and 7) from Fulham.

In 2011, 99-year old Miriam Julier recalled her time at the orphanage in the 1920s, as recounted by her daughter, June Martin:

In Stedham she lived in Myrtle Cottage opposite the green with 8 or so other orphans, including a baby of 6 months whom they called Baba. The initial woman in charge was quite unkind, but soon after mum arrived a woman called Miss Belchamber took charge and she was very kind and referred to as Auntie.

They were known in the village as the cottage kids. Mum’s best friend was Dorothy and two of the boys were named Albert and Freddy.

Their benefactors were Mr. Scrimgeour and his sister. They were obviously philanthropic and lived at Stedham Hall where she went to a Christmas party every year and received a good present. One year she was given a scooter and scooted down the hill with great glee. I believe the Scrimgeours ran a second establishment for ‘crippled’ children.

The children went bare foot except on Sundays when they wore boots and made significant noise when entering the church. All the children attended church every week – morning one week and evening service the next.

They were fed and cared for and most girls went into service at age 13 years – boys often sent to Canada.

None of the residents attended school. A teacher came every day at 4.30p.m. and they had tuition for two hours and home-work was set. I don’t know if this was arranged by the local school or private. The G.P. came periodically to check them out and there were medical and social reports.

Nursing career

In the mid-1890s, Ethel trained as a nurse at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London. In 1897, she came top in the examination results and won the gold medal funded by the Worshipful Company of Clothworkers. Her reports from ward sisters during her training described her as “punctual”, “most kind and attentive”, “always obedient”, “clean and neat”, “tactful and capable” and “devoted to the children”. At the 1901 census, she is recorded at St Bartholomew’s Hospital as one of 21 (nursing) sisters.

In 1904, she established her Home for Delicate Children at Pigeon Hill, between Woolbeding and Redford, to the north-west of Midhurst, Sussex. At the home, she cared for children with tuberculosis and other illnesses, as a small-scale sanatorium; many of the children were orphans from London. The home was little more than half a mile from The King Edward VII Sanatorium, which opened in 1906, soon after she started her work at Pigeon Hill, although there appears to have been no formal connection between the two establishments.

At the 1911 census, Ethel was living at The Lair, a cottage close to Pigeon Hill Farm, together with two staff from the home and two young girls, including her niece, Annie (daughter of Alexander Carron Scrimgeour), aged 5. [Sadly, Annie died at Pigeon Hill from whooping cough in February 1919, aged 13.]

At the home itself, the census lists 43-year old Mary Selina Cowler as the sister in charge with six staff, and 14 patients (nine girls and five boys) aged between 5 and 17. The children all came from London or the Home Counties, and most were probably orphans.

In the 1921 census, Ethel (transcribed as “Ethel Perrington”) was living at Pigeon Hill (now 56 and described as “Hospital sister and farmer”) with 9 children (aged between 3 and 11), plus 25-year old Janet Smith, from Bethnal Green, described as “adopted daughter”, five staff and ten other visitors or boarders many of whom were recorded as “out of work” or “incapacitated”.

Ethel was living at The Lair at the time of the 1939 register, when her occupation was given as “Hospital sister, retired”. In the home itself, the staff included the matron, Florence Aston, with her husband, Oliver, a market gardener and their 14-year old son, Trevor, a pupil at Midhurst Grammar School. [Trevor Aston (1925–1985) went on to have a career as an academic at Oxford University.] The patients included 71-year old Elizabeth Bellingham, who had been recorded as a cook at the 1911 and 1921 censuses. As well as Elizabeth Bellingham, most of the other patients were also elderly.

In Stedham & Iping Remembered (2012) by Christine Dicks, Colin Dunne and Sanchia Elsdon, a former resident of the home, Marjorie Bishop, recalled her time there:

I didn’t go to school until I was six because I had tuberculosis of the bones and had my finger off for it, but I did get better. I went to Scrimmiges up at Redford. It was a home for children that weren’t very well. All lovely fresh air facilities and good food; cod liver oil as well, which I didn’t like very much!

Diana Forshall, whose husband Peter was the son of Isabella Scrimgeour, Ethel’s sister, recalled:

When I first met my husband Peter, he took me to see his aunt Ethel, who, although she came from a very well to do family, had a number of crippled children to live in her house at Redford. They had TB and other childhood illnesses.

Politics

Ethel probably first came into contact with William Joyce and his second wife, Margaret, as a result of his friendship with her brother, Alexander Carron Scrimgeour. They were frequent visitors to Pigeon Hill and “developed a particular liking for … its comfortable life-style”.

Alexander had been the principal financier of Joyce and his National Socialist League, from its foundation in early 1937 to Alexander’s death in August that year.

Following her brother’s death, Ethel (described by Joyce’s biographer, Colin Holmes, as “wealthy on her own account and holding convinced fascist and anti-Semitic opinions”) took over the mantle. She remained loyal to Joyce and kept in regular correspondence with him until his execution for treason in January 1946.

Shortly before William and Margaret Joyce left England for Germany in August 1939, Margaret visited The Lair to say goodbye. She brought with her some belongings, including William’s pistol, which she buried under a tree close to the house. On reaching Berlin, one of the couple’s first acts was to send Ethel a postcard confirming their safe arrival. When Special Branch officers called on her searching for Joyce, they were too late.

After the war, Ethel travelled up to London every day to attend Joyce’s appeal hearing at the House of Lords. While in prison awaiting execution, Joyce continued to write to Ethel; on 28 December 1945, he wrote:

I trust, like you, that the works of my hand will flourish by my death; and I know that there are many who will keep my memory alive. The prayers which you and others have been saying for me have been and are a great source of strength to me: and I can tell you that I am completely at peace in my mind, fully resigned to God’s will, and proud to have stood by my ideals to the last. I would certainly not change places either with my liquidators, or with those who have recanted. It is precisely for my ideals that I am to be killed. It is the force of ideals that the Hebrew masters of this country fear; almost everything else can be purchased by their money: and, as with the Third Reich, what they cannot buy, they seek to destroy: but I do entertain the hope that, before the very last second, the British public will awaken and save themselves. They have not much time now.

Following Joyce’s execution, Ethel wrote a letter of consolation to Margaret:

He was too great a man to be allowed to live and I felt sure the Jews were too powerful to allow him to.

In The Meaning of Treason (1949), Rebecca West describes Ethel as “a tall and handsome maiden lady given to piety and good works, whose appearance was made remarkable by an immense knot of hair twisted on the nape of her neck in the mid-Victorian way”. She continues:

[She] treated Joyce like a son. She let him use her country house as a meeting-place for the heads of his organization, and entertained him there so often that it was one of the first places searched by the police at the outbreak of war when they found that Joyce had left his home.

Then over eighty and crippled by a painful disease, [she] rose from her bed to travel up to London, an apocalyptic figure, tall and bowed, the immense knot of hair behind her head shining snow-white, and went to see William Joyce in prison. She returned weeping but uplifted by his courage and humility and his forgiveness of all his enemies and his faith in the righteousness of his cause.

Death

Ethel Scrimgeour died at the Midhurst Cottage Hospital on 12 January 1953, aged 87. The causes of death were recorded as anaemia, intestinal haemorrhage, scurvy and broncho-pneumonia.

She was buried at St James Church, Stedham on 16 January.

Her gravestone bears the inscription:

“But the greatest of these is charity”

(1 Corinthians 13:13)

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk:

1871 England Census

1881 England Census

1891 England Census

1901 England Census

1911 England Census

1939 England and Wales Register

England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966

London, England, Births and Baptisms, 1813-1906

U.K., City and County Directories, 1600s-1900s

West Sussex, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1995

Bognor Regis Observer. 17 January 1953. Death of Miss E. Scrimgeour

Chichester Observer. 23 June 2013. Ethel Scrimgeour: A Friend to Midhurst’s Sick Children and to “Lord Haw-Haw”

Elsdon, Sanchia & others (2012). Stedham & Iping Remembered, a Walk Back in the Past Through Two Villages

Findmypast.co.uk: 1921 Census of England & Wales

Geni.com: About Ethel Scrimgeour

Gravelroots.net: Miriam Emily Julier – born 1912, Mile End, London

Holmes, Colin (2016). Searching for Lord Haw-Haw. Routledge. pp.120, 122, 159, 175, 368, 371, 376. ISBN 978-1-138-88886-9.

Laity, Paul (8 July 2004) “Uneasy Listening”. London Review of Books. Vol. 26. No. 13.

Mourning the Ancient.com: William Joyce, The Truth

Thompson, Paul (Spring 1995). “The Life and Death of Trevor Aston”. History Workshop Journal. Vol. 39: p.250.

Waifs & Strays: Ethel Scrimgeour: A friend to Midhurst’s sick children and to ‘Lord Haw-Haw’

West Sussex Gazette: 22 January 1953. Death of Miss Ethel Scrimgeour

West Sussex Record Office:

PH 29883: Children from Pigeon Hill Home for Delicate Children having a picnic

PH 29884: Woolbeding: Matron and staff of Pigeon Hill Home for Delicate Children

West, Rebecca (1949). The Meaning of Treason. Penguin. pp. 35 & 36.

Photo credits

Pigeon Hill House: Savills: Pigeon Hill House, Redford

Grave stone: Dawn Cansfield, St James Church, Stedham