Part of the “Crime & Punishment in Cocking in the Nineteenth Century” series

Late in the evening of 22 January 1876, the body of 19-year old George Marshall was discovered on the edge of Chichester Hill, Midhurst. George had spent the evening at a beer house in Midhurst in the company of Thomas Woolford. On the way back to Cocking, the two had started quarrelling, and a fight broke out between them, resulting in George’s death. This is the story of the events of that night, and of the subsequent trial of Thomas Woolford.

The killing

At about 6 p.m. on Saturday, 22 January 1876, George Marshall (aged 19) and Thomas Woolford (aged 27) caught the omnibus from Cocking to Midhurst to visit the shops. Among their fellow passengers was Frederick Farley, the landlord of the Blue Bell Inn at Cocking. Both men had previously worked for Frederick’s father, Henry, as labourers.

After passing the Royal Oak inn, and starting the final descent into Midhurst, the omnibus “broke down” and was unable to complete the journey. The three men helped detach the horses from the omnibus, and led them to the bus depot in Petersfield Road.

Farley left the men at the depot, after which Woolford visited the neighbouring Omnibus & Horses beerhouse (on the corner of Petersfield Road and Rumbold’s Hill), while George Marshall went to the butchers to purchase some meat, before also going to the beerhouse, getting there at about 8:00 and joining Thomas Woolford and his brother James in the smoking room. Later in the evening, the brothers, Thomas and James had an argument about some money (a “few shillings”) that Thomas owed their father, during which George Marshall agreed with James that Thomas should repay the debt. The argument became rather heated, when the landlady, Mrs. Emily Puttick, advised them to be quiet and not to make a disturbance. At this point, it would appear that no threats had been made by any of the men.

Shortly after, James left saying that his brother was being “disagreeable”. Another customer, Benjamin Dabbs, left the bar at about 9:30; as Dabbs made his way out, Thomas came to the bar door and said, “I’m going to have a ____ go in, presently.”

Thomas Woolford and George Marshall left the beerhouse together at about 10:00; neither man was drunk, and both appeared to be quite amicable. According to Woolford, the two men tried to take a shortcut through the yard of the Spread Eagle hotel, but the gate into Chichester Road was locked. He then went through the hotel to get out, leaving George behind.

At about 10:30, Sarah Burt, who lived in a cottage in Chichester Road, heard two men having an argument as they passed her house going towards Cocking. She heard one man say, “Just as you like”, to which the other replied “Come on up here”. The voices then passed on before, a few minutes later, she heard shouting from about 60 yards up the hill. As men often came past her house making a commotion, she thought little of it at the time.

Thomas Woolford arrived at his lodgings in Cocking at about 11:45. His landlady, Harriet Burrows (or Burroughs) asked him where he had been and why he was so late coming home. Woolford replied that he had been into Midhurst and had “left his partner behind”. He went on to say that his partner was George Marshall and that he had last seen him following him up Chichester Hill.

At about 11:00, a group of men were making their way home towards Cocking, when one of them, James Tribe, stumbled across a body lying partly in the ditch on the side of Chichester Hill. He called his companions, and they soon realised that the man was dead. The police were called and were quickly in attendance, and moved the body into the road to examine it, when one of the men identified the corpse as that of George Marshall. A doctor was also called, who confirmed that the man was dead, before the body was carried to the Spread Eagle, a distance of 390 yards (356 metres) from where the body was found.

Several of the men then visited the home of George Marshall and told his family about his death, before going to Thomas Woolford’s lodgings, where they arrived at about 12:30 on Sunday morning. Woolford was asleep and refused to get up. Early next morning, Mrs. Burrows challenged Woolford who again refused to talk about what had happened, before the police arrived to take him into custody.

The Coroner’s inquest

On Monday, 24 January 1876, a Coroner’s inquest was opened at the Spread Eagle Hotel under Frederick J. Malim, West Sussex county coroner.

At the inquest, after William Marshall (the father of George) had confirmed the identity of the deceased, the events of the fateful evening were gone through at some length, before the doctor who had been called out, Dr. Robert Orme M.R.C.S. gave evidence as to his findings from his initial examination of the body. He reported that he had found bruises around the trachea, three on the left and one on the right, and a bruise on the hip There was blood on the face and hands and several scratches on various parts of the body, all of which were indications that the deceased had been involved in a fight and had then been held down in the dirt and strangled.

At the re-convened inquest on Friday, 28 January, Dr. Orme returned to the stand to report on the findings of his post-mortem. These revealed that a bone in the trachea had been broken directly under the bruise on the right of the neck, which was probably caused by a thumb pressing hard. There was also bruising on the forehead and cheek, as if from a punch.

Mrs. Harriet Burrows, Woolford’s landlady then gave evidence as to the state of Woolford’s clothing on his return on Sunday morning. His clothes were very dirty, with his coat “bedaubed” of mud down the front and sleeves, while the knees of his trousers were wet as if he had been saying his prayers. The coat and trousers, together with a hat and scarf, had been taken away by the police.

The hat was then produced in evidence together with a similar hat found near the body. George Marshall’s sister, Jane, and sister-in-law, Sarah, both examined the two hats and declared that the hat found in Woolford’s possession belonged to their brother, this one being a different shape and newer, less scruffy, than the other.

At the conclusion of the inquest, the jury found that “the deceased met with his death by strangulation, and that Thomas Woolford was guilty of manslaughter”.

Committal hearing

The committal hearing was held at the office of the clerk to the magistrates in Midhurst on Monday 7 February 1876, with Admiral Edward Tatham, C.B. presiding.

Little in the way of new evidence was produced at the hearing. The police constable who had attended the crime scene reported the circumstances and said that he searched the dead man. In his pockets were a knife and a purse containing 17s 3¾d, while his bundle contained the meat that he had purchased earlier. He added that there were no marks of violence on the face of the accused.

At the end of the hearing, which lasted nearly seven hours, Woolford was formally committed for trial.

The trial

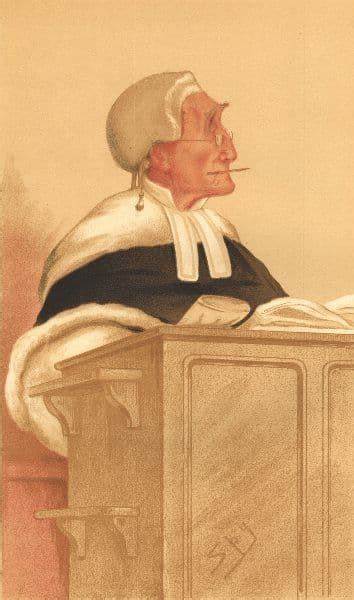

The trial took place at the Spring Assizes on the South-Eastern Circuit at Lewes Crown Court on 11 March 1876 before Sir Anthony Cleasby, Bart., when Thomas Woolford was indicted for the wilful murder of George Marshall.

The prosecutor presented the evidence as already heard at the inquest and committal proceedings. He then summed up, stating that it was clear that the deceased was killed by violence on the part of the prisoner. The only question was the degree of premeditation and whether the prisoner had any malice towards the deceased when they left the beerhouse. In his opinion, the lack of any marks on the accused and the level of violence committed against the deceased pointed towards a deliberate act of murder.

The defence counsel argued that the evidence was mainly circumstantial and there was no hard evidence that the accused had been involved in the fight that led to the death of George Marshall. Even if it was accepted that he had been involved, there was no evidence of premeditation nor malice, and it was simply a quarrel between two men that had got out of hand, leading to one being killed. This would be merely manslaughter.

The judge then addressed the jury saying that this was rather a singular case. The questions for the jury to decide were whether or not the prisoner committed the act of homicide and, if he did, whether it was murder or manslaughter . After summarising the case against Woolford, he then explained the difference between murder and manslaughter at considerable length.

The jury, after a brief consultation, found the prisoner Guilty of Manslaughter.

The judge then discussed the question of sentence. Addressing the accused, he said,

“… in using the violence you did, you ran a great risk of losing your life, for I am not at all sure that, on a stern administration of the law, it might not be deemed a case of murder. It is a humane verdict, and I think a proper one, which reduces the offence to manslaughter.

But still, though only manslaughter, it must be punished as a very bad case of manslaughter, for though there was not that malignant intention which would have made it murder, deadly violence was used in the course of the struggle. The practice of using this sort of savage, deadly violence is a disgrace to the country, and it is the duty of the Judges to endeavour to put a stop to it by making severe examples in cases where the circumstances appear to justify it.

…the sentence upon you is that you be kept in penal servitude for 15 years.”

Sources

Brighton Guardian:

26 January 1876 Midhurst

15 March 1876 The Alleged Murder at Midhurst

Grantham Journal:

18 March 1876 Charge of Murder

Horsham, Midhurst, Petworth & Steyning Express:

25 January 1876 Midhurst: A Great Consternation

1 February 1876 The Suspected Murder at Midhurst

1 February 1876 Adjourned Inquest

8 February 1876 Committal of the Accused

The Times (London):

31 January 1876 Inquests

13 March 1876 Spring Assizes

Picture credits

Midhurst Omnibus Office and The Omnibus & Horses: Both from “Charles White – 19th and early 20th century Midhurst in old photographs.” (1972)

Sir Anthony Cleasby (Vanity Fair): Wikimedia Commons

George Marshall

George Marshall was born in Cocking in early 1856, the youngest of four sons (and seven daughters) born to William Marshall (1808–1896) and his wife Sarah, née Poat (1817–1878). William (an agricultural labourer) and Sarah had married at Heyshott on 3 October 1835.

George was baptised at Cocking church on 16 March 1856.

At the time of the 1871 census, William and Sarah were living at “The Street”, Cocking with all four sons and their youngest daughter, Dora aged only 5, and a 14-year old grandson, William. Both the eldest son, William, aged 33 and George, aged 15, were described on the census as “Invalid – pauper”.

George was buried in Cocking churchyard on 26 January 1876. The burial register has a note alongside his name: “Murdered”.

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk:

1861 England Census

1871 England Census

West Sussex, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1920

West Sussex, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1995

West Sussex, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1936

FreeReg.org.uk

Cocking parish register. 16 March 1856. Baptism of George Marshall.

Cocking parish register. 26 January 1876. Burial of George Marshall

Thomas Woolford

Thomas Woolford was born in Stedham in mid-1848, the eldest of eleven children born to Thomas Woolford (1826–1905) and his wife Sarah, née Strotton (1829–1906). Thomas senior (an agricultural labourer) and Sarah had been married at Stedham on 24 January 1848.

Thomas was baptised at Easebourne church on 13 August 1848.

At the 1871 census, Thomas was living at Fernhurst where he was employed as a farm labourer, while his parents were living at Linch farm, near Bepton, with their seven younger children.

Following his imprisonment in 1876, Thomas was an inmate at Chatham prison at the 1881 census. By the time of the 1891 census, he had been released from prison and was living with his parents at Bepton, where he was again employed as a farm labourer.

On 5 May 1894, Thomas Woolford, aged 45 (although the marriage register gives his age as 41) married 27-year old Kate Poat at Bepton parish church. Kate was the granddaughter of James Poat (1807–1852) who was the elder brother of George Marshall’s mother, Sarah (1817–1878).

At the time of the marriage, Kate already had two children: Mary Anne (born 1887) and Thomas (born 1893). There were two further children of the marriage: William (born 1894, died 1900) and Harry (born 1896)

Thomas junior served with the Royal Sussex Regiment in the First World War. He died of wounds in Belgium on 9 October 1918 and is buried at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery near Ypres, and commemorated on the Tillington war memorial.

Thomas Woolford died in 1932 (death registered at Midhurst in the April 1932 quarter), aged 83. His widow survived him by 17 years and died in 1949 (death registered at Midhurst in September 1949 quarter).

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk:

1881 England Census

1861 England Census

1871 England Census

1881 England Census

1891 England Census

1901 England Census

1911 England Census

England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892

West Sussex, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1920

West Sussex, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1936

Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Private Thomas Woolford

FreeReg.org.uk

Easebourne parish register. 16 March 1856. Baptism of Thomas Woolford

Bepton parish register: 5 May 1894. Marriage Woolford – Poat