Part of the “Crime & Punishment in Cocking in the Nineteenth Century” series

The following talk was delivered at Cocking Village Hall on 24 October 2023. It is based on this series of articles, although there were occasional editorial amendments to make the talk more suitable for a general audience.

Thankyou Andy for the introduction and for all the hard work you put into organising these talks. Thanks also to you all for turning out this evening.

I would also like to thank my granddaughter Kitty for her excellent poster; but special thanks must go to Darron Carver for “suggesting” that I prepare this talk.

As a result of the challenge laid down by him at his talk in January, I have spent countless hours in the West Sussex record office going through their records of the Quarterly Assizes, and scouring the British Newspaper Archive for stories about Cocking’s criminal past. In the 100 years of the nineteenth century, I found close on 150 different stories involving Cocking, either as the location of the crime or the home of the people involved (or both).

The crimes vary from murder and rape at one extreme down to more trivial crimes, such as unlicenced dogs and allowing cattle to roam on the highway. You’ll be pleased to hear that I don’t intend to discuss every case! I have picked out the more interesting crimes, or those that were reported in most detail, and will try to bring out some themes.

There are too many interesting cases to talk about this evening, so I will cover the first half of the century, and will come back in January to continue the story.

Before talking about individual cases, let’s have some background.

The rural poor

At the start of the nineteenth century, England as a whole, and Cocking in particular, was a very feudal society. At the top was the landowner, William Poyntz who inherited the Cowdray estate on the death of his brother-in-law, the 8th Viscount Montagu, in 1793.

At the start of the nineteenth century, England as a whole, and Cocking in particular, was a very feudal society. At the top was the landowner, William Poyntz who inherited the Cowdray estate on the death of his brother-in-law, the 8th Viscount Montagu, in 1793.

Below him were the yeoman farmers, including John Challen who owned Crypt Farm, and his brother Stephen who had Brook House farm which stood on the hillside opposite the church, later given to his son, Benjamin. Alongside them in rank was the parson, Melmoth Skynner who had been appointed vicar in 1798 and would look after the spiritual needs of the villagers for 25 years.

The lower middle class included the blacksmith, the millers, the innkeeper and the village carpenter, who doubled up as undertaker.

Beneath these worthy gentleman came the 100s of agricultural labourers and their families, who were trying to eke out an existence with insecure employment and very low wages, living in unsanitary homes with the perils of old age and ill health to face.

In November 1825, on his Rural Rides through southern England, William Cobbett passed through Rogate where he met a farm labourer repairing hedges. This young man had found it hard to get regular work, as the farmers preferred to employ married men with children, in order to avoid raising the Poor Rate. The labourer was paid seven pence for a day’s work, enough to buy 2¼ pounds of bread (roughly 1¼ loaves), for six days a week, with no wages on Sunday.

In November 1825, on his Rural Rides through southern England, William Cobbett passed through Rogate where he met a farm labourer repairing hedges. This young man had found it hard to get regular work, as the farmers preferred to employ married men with children, in order to avoid raising the Poor Rate. The labourer was paid seven pence for a day’s work, enough to buy 2¼ pounds of bread (roughly 1¼ loaves), for six days a week, with no wages on Sunday.

“The poor creature here has seven-pence a day for six days in the week to find him food, clothes, washing, and lodging! It is just seven-pence, less than one half of what the meanest foot soldier in the standing army receives; besides that the latter has clothing, candle, fire and lodging into the bargain!”

Matters had improved slightly by March 1837, when the Parliamentary Select Committee on the Poor Law heard evidence of the financial circumstances of several labourers of good character from villages around Petworth. One of the men was William Kingshott, a married man with six children under 12 (including twin nursing babies) and a son aged 16.

Matters had improved slightly by March 1837, when the Parliamentary Select Committee on the Poor Law heard evidence of the financial circumstances of several labourers of good character from villages around Petworth. One of the men was William Kingshott, a married man with six children under 12 (including twin nursing babies) and a son aged 16.

The labourer’s wages for a normal week’s work were 10s a week; the 16-year old son earned a further 3s, making the total family income 13s.

The family expenditure on food was 9s 4d for a bushel of flour to make bread, a pound of butter at 11d, two pounds of cheese at 1s 2d, two ounces of tea, 8d, and two pounds of sugar, 1s. (She needed extra sugar to feed the twins.)

Thus the total weekly expenditure on food alone was 13s 1d. A small amount of food could be grown in the cottage garden. The family had been given a pig by a friend, but were unable to buy meal to feed it – the pig was loose on the common.

At harvest time, the weekly wages would double; other income could come from gleaning and whatever small amounts the younger children could earn. The rent for the family home was £4 4s a year (1s 8d per week) which was paid at harvest time. Any expenditure on clothing, candles, firewood etc. would also have to come from the harvest earnings.

In December 1844, the Brighton Herald published “An Address to the Labourers of Sussex”, which included the following:

Let us respectfully ask the three gentlemen whom we maintain in luxury out of our labour: the landlord, clergyman and farmer, not to grind our faces as they hitherto have done. Let us pray them to stretch forth their hands to save us from that squalid poverty towards which we are approaching with gigantic strides. Our condition gets worse every year.

There are those that think that bread alone is sufficient to keep a man’s strength up, who has to labour in the fields. I wish that those that think thus would accompany me on a cold winter’s morn, with the bitter biting north wind blowing in his face, with rain, sleet, or snow. Let him work in the field for five hours, and afterwards sit under a wet cold hedge and eat for his dinner a bit of bread day after day.

Is it any wonder that, in an effort to improve their lot, many turned to what we today would consider petty crime: a bit of poaching (rabbits and birds), stealing firewood or fruit from trees, etc. Most got away with it, but when they were caught they ended up in front of the magistrates at the Quarterly Assizes, generally at Petworth.

Hard Labour

Following the abolition of capital punishment for most crimes, the punishment generally handed down to convicted criminals was a period in the House of Correction with Hard Labour.

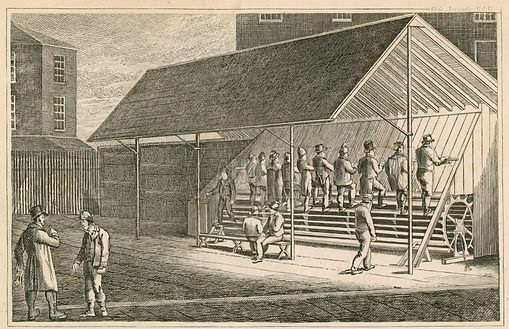

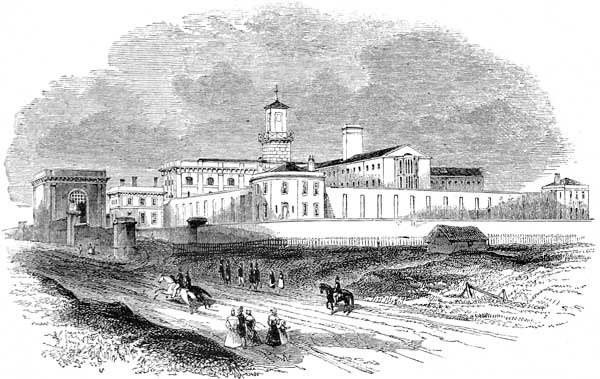

The Petworth House of Correction stood on the southern side of the town. Whilst at the prison, the inmates were expected to be silent and spent almost all of their time in isolation. Both men and women were imprisoned here and, during their stay, had to complete backbreaking tasks or face additional punishment: the most infamous of these tasks was the treadmill, introduced in 1818.

The treadmill was rather like a watermill’s wheel with 24 paddles placed 18 inches apart. The men would walk 10 abreast for 10 hours in the summer and 7 in winter; if you fell, you were in mortal danger! Each prisoner performed 36 rotations, at one rotation per minute(i.e. 864 steps) and then rested for about twelve minutes. After the rest period the prisoner returned to the treadmill to continue his stair climbing punishment for another 36 minutes, and so on. The prisoners were allowed one hour for breakfast and two hours for dinner. In a typical day, a prisoner would climb the equivalent of over 10,000 feet.

The treadmill was rather like a watermill’s wheel with 24 paddles placed 18 inches apart. The men would walk 10 abreast for 10 hours in the summer and 7 in winter; if you fell, you were in mortal danger! Each prisoner performed 36 rotations, at one rotation per minute(i.e. 864 steps) and then rested for about twelve minutes. After the rest period the prisoner returned to the treadmill to continue his stair climbing punishment for another 36 minutes, and so on. The prisoners were allowed one hour for breakfast and two hours for dinner. In a typical day, a prisoner would climb the equivalent of over 10,000 feet.

Some prisoners were also punished by solitary confinement, when a screen was placed between prisoners. A regime of total silence was strictly enforced.

If the guards wanted to make things harder; they would screw down the brakes – hence the term “screws” for prison warders.

That’s enough background; let’s look at some actual crimes.

John Varndell

The earliest case I came across was that of John Varndell, who seemed to be a serial offender. He was a carter by trade and carried goods from Midhurst to Guildford and on to the markets in London. When there was insufficient trade from the local farmers, he would obtain his cargoes by helping himself to produce from farmers’ barns.

On Saturday 2nd March 1805, he broke into a barn belonging to a Mr Lunn at Cocking and stole three sacks of oats, before moving on to Mr Newman’s farm where he stole four bags of seeds. He stashed the sacks from both break-ins at Mr Challen’s barn, meaning to collect them later, so that he could transport them to London. Unfortunately for him, the sacks were soon discovered; a guard was placed in the barn, and when Varndell came up to the barn the following evening, he was spotted but managed to escape empty handed.

He was arrested the following week, near Ripley, Surrey, making his way from Guildford to London, with a wagon load of stolen hay and sacks of beans. At the Guildford assizes in April, he was sentenced to 12 months hard labour.

He was back in front of the magistrates in November 1812 on a charge of “misdemeanour” and sent to the House of Correction for three months, and to be whipped in Petworth market place once each month. At the end of his sentence, he was unable to find suitable sureties for good behaviour and languished in jail for a further two years.

No sooner had he been released than he was back in court again, in April 1815 on a charge of assaulting his wife, Henrietta. He was again unable to find someone to stand surety for him, so he was locked up for a year, before being delivered to the Cocking overseers, after which he disappeared from the records.

The next story has tenuous links with Cocking, but I had to include it.

The Highwayman Jim Allen and the Murder of Captain Sargent

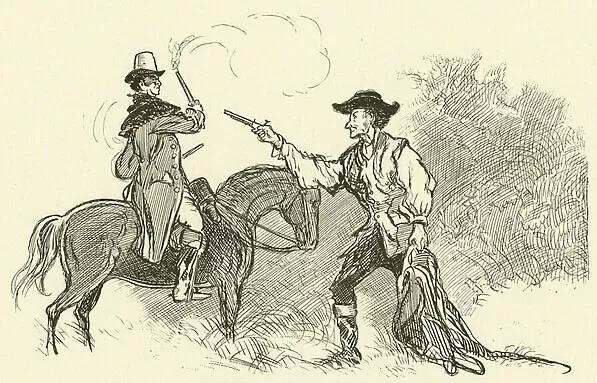

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, travellers through and around the South Downs were frequently held up by armed highwaymen, who would demand that the traveller hand over all his money and valuables in exchange for having their life spared. In late 1807, one such footpad infested the roads between Chichester and Arundel in the south, and Midhurst and Petworth in the north, relieving merchants and farmers of their heavy purses as they returned from market, until the fateful day when a robbery set in motion a chain of events which would end in tragedy and two killings.

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, travellers through and around the South Downs were frequently held up by armed highwaymen, who would demand that the traveller hand over all his money and valuables in exchange for having their life spared. In late 1807, one such footpad infested the roads between Chichester and Arundel in the south, and Midhurst and Petworth in the north, relieving merchants and farmers of their heavy purses as they returned from market, until the fateful day when a robbery set in motion a chain of events which would end in tragedy and two killings.

At about midday on Sunday 1st November 1807, Thomas Rhoades, a lawyer who had just completed a year as Mayor of Chichester, was nearing the top of Cocking Hill as he was riding to Midhurst, when the highwayman jumped out from behind an oak tree and grabbed the horse’s bridle. He pointed his pistol at Rhoades and demanded that he hand over his valuables. Rhoades pulled out his gold watch and a one pound note and handed these over to the villain, who made off across the downs towards Graffham.

Rhoades soon recovered from the shock of being robbed, and returned to Singleton to the home of his friend, George Tyson, at Drovers House. A messenger was sent to Chichester to notify the magistrates of the robbery while Tyson and his coachman, Charles Walker, made for Midhurst, where they were joined by a Mr. Symons and William Poyntz, the owner of Cowdray Park. Suspecting that the highwayman was Jim Allen from Graffham, an army deserter who was already wanted for shooting at a militiaman near Arundel the previous week, the four men rode direct to Allen’s father’s house at Graffham. Finding this empty, they rode on to Lavington House where they asked the squire, John Sargent (also the parish priest) to post a watch at the cottage.

John Sargent’s brother, 25-year old George Sargent was a Captain in the 9th Regiment of Foot, who had just returned after escaping from captivity in France. Captain Sargent joined the other four men, and they rode to the top of the downs, where they split into two groups, with Capt. Sargent accompanying Mr. Symons.

Poyntz, Tyson and Walker headed in the direction of Tegleaze wood, when Poyntz spotted a man answering the description of the fugitive. When Poyntz was within 20 yards of the man, he challenged him, before the footpad ran off. Poyntz was convinced that this was their prey, so called for the others to join him in the pursuit. The fugitive then pulled out his gun, before fleeing into some thick bushes.

By now Capt. Sargent had joined them and the men surrounded the thicket, when Walker spotted a hat and gloves on the ground, and dismounted to examine them. As he did so, he saw the fugitive in the bushes about two yards away, lying flat on his stomach with the muzzle of his gun pointed at Walker.

Seeing the gun cocked, Walker jumped sideways and called out. The man sprang up and ran further into the woods without hat or shoes. After a chase, only Captain Sargent was able to stay close to the fugitive. Poyntz was unable to see either man but heard Sargent say:

“Ah, Jim, I have found you—l don’t want your life, but you must surrender yourself. If you don’t stop, I will shoot you – but no, I can’t shoot a man. I won’t take away your life.”

The villain responded: “Damn you, then, I’ll take away yours.”

Poyntz was making his way towards the sound of the words, when he heard two gunshots about 30 yards from him in the thickest part of the coverts. By the time that he had reached the spot, the culprit had fled, but Sargent had fallen from his horse and was lying dead on the ground.

By now, it was getting dark, so they carried the body to Lavington House, and abandoned the chase for the night.

The next day, a large search party was formed at Graffham, with newspapers reporting that there were as many as 300 men from Petworth and Arundel and surrounding areas, many of whom were armed with guns and others with clubs and prongs, plus another 100 Dragoons on horseback. The woods in all directions were searched and there were a few brief sightings when shots were fired, but without effect.

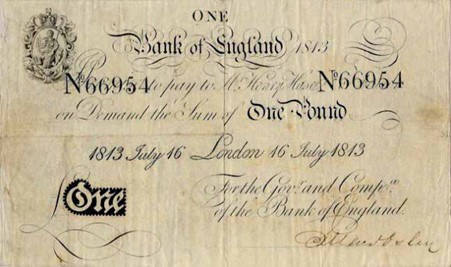

Late in the day, as the pursuit was about to be called off again, a group of men found fresh footprints leading towards the woods to the north-west of Graffham. They followed the trail to the edge of a small stream. They heard a rustling in the bushes and spotted a man about six yards away, climbing out of a small brook where he had been hiding, holding his pistol. One of the party immediately fired his gun and the man fell, uttering the words: “Oh, Lord! Oh, my Lord!” in a tone of agony and despair. Another man fired a second shot and Allen fell back into the water. He was dragged out and left on the grass, where he lay on his back gasping for about fifteen minutes before he died. After he had died, they searched his pockets and found Mr Rhoades’ pocket watch and the stolen one pound note.

The body was taken to the public house in Graffham, where it was confirmed as that of James Allen. At the subsequent inquests, the coroner returned a verdict of “Wilful Murder” by Allen, in respect of Captain Sargent and of “Justifiable Homicide” in respect of James Allen.

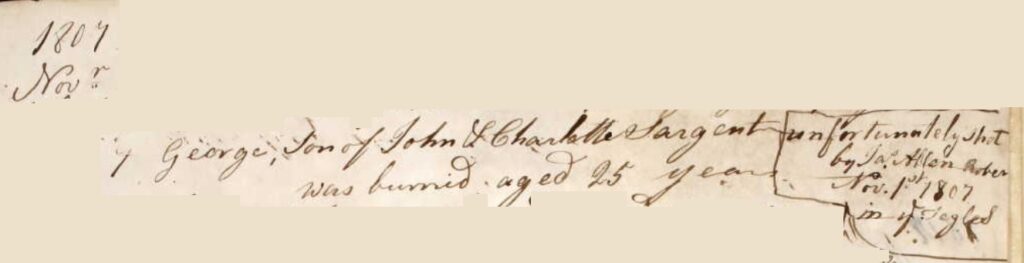

George Sargent was buried in Woolavington churchyard on 5 November. The burial register has a note saying: “unfortunately shot by Jim Allen, robber, Nov. 1st, 1807, in Tegleaze.”

Allen was buried at St James’s church, Heyshott on 15th November 1807. The parish register includes a note: “A Deserter who shot and killed Capt. George Sargent was buried at Heyshott“. The grave was said to be marked by a small stone on which were scratched the initials “J.A.”

On Tegleaze Down there is a magnificent beech tree planted at the spot where Captain Sargent was killed, with a wooden plaque engraved “Sargents Tree”.

Mary Andrew

One of the most distressing cases that I came upon during my researches was that of Mary Andrew, who was frequently kicked and beaten by her husband, Henry.

29-year old Mary Penny (a widow) married 42-year old Henry Andrew from Cocking in Islington, London on 4th August 1814.

Within a fortnight of the wedding, Henry started to hit Mary and in September the following year she took out a summons against him for assault.

In her testimony to the magistrates at Chichester, she said that soon after the wedding, he began to “beat me and to treat me with cruelty, and at various times kicked me and beat my head against the wall with great violence and threatened to do for me”. She also testified that he was “endeavouring to starve me by withholding from me the common necessities of life”.

In early September 1815, they had an argument about money when he kicked her violently on her legs and beat her head against the wall several times. He twisted her arms and pinched them with great violence resulting in bruising and discolouration to her legs and left arm. Her head was also severely bruised and sore. She took over a fortnight to recover from the effects of the injuries.

At the magistrates hearing on 21 September, Henry was bound over to keep the peace in his own surety of £100 (about £11,000 today).

Following the court case, Mary was too frightened to return home and went to live with friends at West Lavington. Henry refused to allow her to take any of her clothes or other possessions with her, other than the clothes that she was wearing.

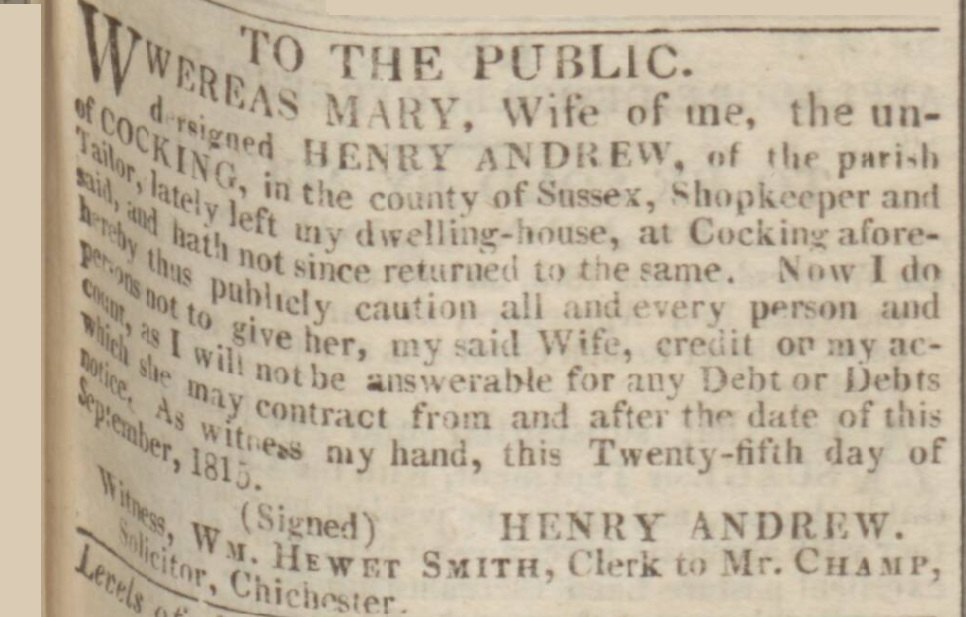

On 9 October, Henry placed an advertisement in the Sussex Advertiser, saying:

On 9 October, Henry placed an advertisement in the Sussex Advertiser, saying:

TO THE PUBLIC

WHEREAS MARY, wife of me, the undersigned HENRY ANDREW, of the parish of COCKING in the county of Sussex, Shopkeeper and Tailor, lately left my dwelling-house, at Cocking aforesaid, and hath not since returned to the same. Now I do hereby thus publicly caution all and every person and persons not to give her, my said wife, credit on my account, as I will not be answerable for any Debt or Debts which she may contract from and after the date of this notice.

As witness my hand, this twenty-fifth day of September, 1815.

(signed) HENRY ANDREW

In February 1816, Mary was told that Henry was now prepared to let her come to collect her clothes, so she returned to the former matrimonial home in Cocking. Immediately she entered the house, Henry jumped on her, kicking her on the legs and beating her head against the wall, screaming abuse at her. He grabbed her arms and twisted them violently, leaving her with a badly damaged hand.

Mary’s screams brought the neighbours running into the house, who pulled her away and took her outside. Henry turned on them, shouting that he would kill her. “To kill her would be no more a sin than to kill a dog.”

Her friends put her on a cart and took her back to West Lavington, with Henry following behind as far as Cocking Causeway, with a bludgeon in his hand, shouting further threats at Mary and her friends.

In April 1816, Henry appeared at the Petworth Assizes and was again bound over, although the sureties had now been reduced to £10 each, put up by four of his family and business friends, including William Shippam a grocer from Chichester.

Various questions arise with regard to this case:

- Why did Mary return to her former home unaccompanied?

- Was Henry required to pay over the £100 surety from the first hearing? If not, why not?

Thomas Purser

On the night of 4th November 1822, Benjamin Challen’s groom placed his brown mare into the stables at Brook House Farm, leaving the door unlatched. The following morning, the groom discovered that the horse was missing. After a thorough search around the farm and village, Mr Challen had hand bills printed and circulated throughout the neighbouring towns and the rest of the county, with a full description of the missing horse.

By the time that the loss was discovered, Thomas Purser, a 32-year old labourer from Todham Farm, near West Lavington, had taken the horse to Lewes where it was sold by auction on the same day, to a Mr Eagles, a farmer from Newhaven.

A day or two later, Mr Eagles saw one of the handbills circulated by Benjamin Challen, and noticed that the horse he had purchased appeared to be identical to the stolen one. He sent a message to Challen, who then travelled to Mr. Eagle’s farm at Newhaven where he confirmed the identity of the horse.

Thomas Purser was soon hunted down, and taken into custody on 10th November. He was brought to trial at the Sussex assizes in Lewes on 24th December in front of Sir John Bailey, on a charge of stealing the mare, valued at £30. Despite his pleas that he had spent the night of the theft “sleeping at the home of his washerwoman”, he was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Justice Bailey sentenced 15 prisoners to death at the assizes, for a range of offences from sheep and horse theft to highway robbery.

On 8th January 1823, the Home Secretary, Robert Peel commuted the death sentences against 66 prisoners from across the country, including Thomas Purser, to transportation for life.

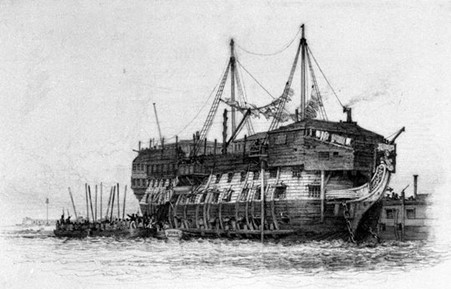

Thomas Purser was kept on board a prison hulk, the former HMS York, in Portsmouth Harbour until 20th May 1823, when he was one of 200 prisoners on board the Albion, as it left the Solent bound for Tasmania, where they arrived on 21st November after 154 days at sea.

No further detail are available of Purser’s time in the penal colony.

During my research, several family names cropped up repeatedly including Marshall, Horton and Farley. One family had three generations who appeared in court, including two who were also sentenced to Transportation to Australia.

The Kingshott family

Benjamin Harwood

Early in the morning of 14th November 1819, Sarah Kingshott was woken at the home in Cocking where she lived with her husband Henry and her two children. Her brother, Benjamin Harwood was at the door and presented her with two beehives, claiming that he had purchased them in Eartham. She didn’t believe his story, but helped him conceal the hives in the attic of the house.

Early in the morning of 14th November 1819, Sarah Kingshott was woken at the home in Cocking where she lived with her husband Henry and her two children. Her brother, Benjamin Harwood was at the door and presented her with two beehives, claiming that he had purchased them in Eartham. She didn’t believe his story, but helped him conceal the hives in the attic of the house.

Later that morning, Joseph Manley came to the house armed with a search warrant and discovered the hives and identified them as having been stolen from his garden at Eartham. either the previous evening or earlier that morning.

Benjamin was soon arrested and taken by cart to the Petworth House of Correction. On 11th January, he appeared at the Petworth Quarter Sessions on a charge of stealing two beehives, value 2s, and 20lbs of honey, valued at 12s. He was found guilty and sentenced to one month in solitary confinement at Petworth.

This story raises several questions:

-

-

- How did Benjamin Harwood transport the hives from Eartham to Cocking, a distance of 10 miles? There is no mention of an accomplice, so presumably he had a horse and cart; the journey on early 19th century tracks would have taken about 4 hours.

- What happened to the bees?

- Was the honey still in the hives when they were stolen?

-

John Kingshott

Fifteen years later, on 6th March 1834, Sarah Kingshott’s 17-year old son John, and his friend, James Lambert appeared at the Petworth Quarter Sessions, on a charge of trespass at Cocking in search of game. Both men were found guilty and fined £1 with 12s costs.

Fifteen years later, on 6th March 1834, Sarah Kingshott’s 17-year old son John, and his friend, James Lambert appeared at the Petworth Quarter Sessions, on a charge of trespass at Cocking in search of game. Both men were found guilty and fined £1 with 12s costs.

In August 1842, John Kingshott was back in front of the court, this time at Chichester, on a charge of assault against the Cocking village constable, Edward Wheatley. John was fined £2 10s.

On 30th October 1842, John Kingshott (now a sawyer, aged 26) and Thomas Thayre were arrested for stealing four bushels of beans, valued at 18s, and a sack, valued at 2s, from George Daughtry. They were tried at the Petworth Quarter Sessions on 6th January 1843, and found guilty.

Thomas Thayre was given a reference of 13 years good character by his employer, and was sentenced to two months hard labour, with the first week in solitary confinement.

John Kingshott, however, was not so lucky. With two previous convictions, he was sentenced to seven years transportation.

John Kingshott was sent to Pentonville Prison where he remained until July 1844, when he was put onboard the SS Royal George, reaching Port Phillip in Victoria four months later, on 15th November.

John Kingshott died in Victoria in 1851, aged 34, shortly after completing his 7 years in the penal colony, and never lived long enough to enjoy his freedom.

William Mills

John Kingshott’s sister, Leah, married Thomas Mills in 1831. Their second child, William, was born in September 1833.

At Bepton on the evening of 30th November 1850, William Hounsome, a shepherd, discovered that three tame rabbits, which he kept in his wood house, had gone missing.

The following day, acting on information received, he went to Chichester and found the skin of one of his rabbits at the home of George Mantle in Somers Town.

Eventually, the trail of the rabbits was traced back to William Mills, now aged 17.

It would appear that William had stolen the three rabbits and taken them home. One had been put in the pot by his mother, and he had taken the other two to Chichester, where he sold them to Thomas Vinson for 1s 2d. Vinson in turn kept one for his dinner and sold the other to George Field.

George Field took the rabbit back to his lodgings, where he gave it to Elizabeth Holden, his girlfriend. She skinned the rabbit and prepared it for the pot, and sold the skin, plus three others, to George Mantle of Somers Town.

At the next Petworth Quarter Sessions, on 2nd January 1851, William pleaded guilty to the theft of the three rabbits, valued at 3 shillings. He was sentenced to six weeks hard labour.

Sadly, William didn’t learn from his time in the Petworth House of Correction, and was back in court six months later. On 3rd July 1851, he appeared at the Midsummer Quarter Sessions, held at Horsham, charged with the theft of six sheep skins, valued at 9 shillings, from Benjamin Challen of Brook House Farm.

William was found guilty and, in view of his previous conviction, was sentenced to be transported for ten years.

By this time, transportation was on the decline and it appears that William was never sent to Australia, but served his sentence at Pentonville Prison.

Harriet Cooper

On 20th November 1824, 19-year old Harriet Cooper walked the 9 miles from Cocking to Petworth for the annual St. Edmund’s Fair, with a basket of pies and rolls for sale.

Trade during the day was brisk until about 5 o’clock in the evening, as it was starting to get dark, when a customer offered her a shilling coin to pay for a one penny roll, for which she gave him a sixpence and ten halfpennies in change. About ten minutes later, the same customer returned to buy a pie, also costing a penny. Again he offered her a shilling coin in payment, for which she gave him eleven pennies in change.

Within five minutes, the customer was back to buy another penny roll, once again offering a shilling coin in payment. By now, Harriet was suspicious and said that she had no more change and could not take his coin.

Despite her suspicions, when another customer offered her a shilling coin to pay for two halfpenny pies, she again accepted it and gave him his change.

With the third shilling, she went to the stall of a Mr Goacher and tried to use it to pay for a bag of nuts. Goacher refused to accept the coin, saying that it was “a bad one”. Now worried that she might have taken three dud coins, she asked Goacher to look at the other two, which he also declared as bad.

She and Mr Goacher then found the special constable, Richard Habbin, and told him what had happened. She and Habbin started to look for the two villains, when the first customer approached her and asked to buy another penny roll. As he reached into his pocket for yet another shilling coin he spotted Habbin, so quickly retuned the dud coin to his pocket and took out a penny to pay for the roll.

Harriet told Constable Habbin that this was one of the culprits – he was soon taken into custody and handed over to the regular constable, John Lucas, who put him into the cage. The prisoner, who gave his name as “John Baker”, was searched and had four shillings, one of which was counterfeit, plus some sixpences and copper coins.

Harriet and Constable Lucas took the three shillings that she had received from “John Baker” and his accomplice, plus the one found on Baker, to John Easton, a silversmith, who confirmed that all four were “false money” and all appeared to have come from the same die.

On 22nd November 1824, Baker appeared before the magistrates on a charge of passing counterfeit coins and was committed to trial at the next Petworth Quarter Sessions. On 11th January 1825, he was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment with hard labour and required to put up £20 surety himself and two other sureties of £10 each for his good behaviour for two years after his release from prison.

Although Harriet was only 19 at the time, she seems to have been incredibly naïve. To have fallen for Baker’s trickery once was maybe unfortunate, but she should have smelled a rat at the second time. Although she finally suspected something was wrong at Baker’s third attempt, she still accepted a dud shilling from a different customer.

Three geese and a gander

On Saturday 29th January 1831, 22-year old William Pollard and 21-year old James Horton went to the farmyard of Thomas Chalcroft at Manor Farm, leaving James’s cousin, 20-year old William Horton at the nearby blacksmith’s shop. The two men drove four geese and a gander from the farmyard into “Heyshott field” where they killed three of the geese and the gander. (It’s not clear what happened to the fourth goose.) Each man then picked up two of the dead birds and took them to the blacksmith’s shop, where James Horton handed his pair to William Horton, and then returned to his lodgings.

The two Williams then took the geese to the lime kilns, where they plucked them and discarded the wings. They hid two of the geese under some straw near Chalcroft’s barn, before William Horton took his share of the plunder to James’s lodgings. Later that day, all three men and James’s wife enjoyed a hearty meal of a pudding and a pie prepared from the two geese.

On the Sunday evening, William Pollard retuned with a sack and removed the other two geese from under the straw and hid them in a hedgerow.

A few days later, a group of men from the village were at the lime kilns when they came across the discarded wings. One of them, John Budd, realising that they probably came from Chalcroft’s missing geese, picked them up, intending to hand them over to Chalcroft, but before he could do so, his friend John Johnson took one of the wings, ripped it to pieces and threw it away.

At about the same time, Thomas Phillips from Singleton found the sack containing the two geese in the hedgerow. Knowing that Thomas Chalcroft had lost some geese a few days before, he took them up and returned them to Chalcroft.

The three men were soon arrested and, on 25th February, appeared ar the committal proceedings at Petworth, with Richard Bingham Newland presiding. By this time, William Pollard had turned “King’s Evidence” and made a full confession of his part in the crime.

Sarah Dearling, whose mother was the keeper of the house where William Horton lodged, told the court that, on the morning after the theft, she “observed white down, such as comes from feathers, upon the head of William Horton”. Horton tried to make light of her comments, but proceeded to comb the feathers out of his hair.

The three man were committed for trial at the Easter Quarter sessions. These were held on Monday 4th April at Petworth with the Earl of Egremont no less presiding. The case against William Pollard was discharged, while James Horton was found guilty of “stealing at Cocking one gander worth 2s 6d and three geese worth 7s 6d, the property of Thomas Chalcroft”, and was sentenced to two months imprisonment with hard labour.

William Horton was acquitted of larceny, but found guilty of receiving stolen property, and also sentenced to two months hard labour.

Like most of these cases, this one raises several queries: for example, how did the men manage to drive the geese away from the farm without them making a racket and wake the farmhouse? Why did the men try to hide the geese, rather than take them home and stash them there?

In September 1835, James Horton was back in front of the magistrates at Chichester, charged with stealing 5 bavins (large logs), valued at 1s 3d, from Richard Bingham Newland (the magistrate at this 1831 hearing). The case was discharged due to lack of evidence.

Another goose

On the evening of Saturday 4th March 1837, Benjamin Challen checked his livestock and saw that his small flock of two saddle back geese and one gander was secure in the meadow at the rear of his house. The following morning, he noticed that one of the geese was missing.

The following Monday evening, William Pollard went to the Swan Inn at Midhurst carrying a basket containing a large goose matching the description of the missing bird. He tried to sell the bird to Elizabeth Lithgow, the daughter of the landlord. She agreed that he could leave the basket there and come back next evening to speak to her father.

On Tuesday evening, William Pollard returned to speak to John Lithgow, the landlord, who refused either to buy the goose, which weighed 16lb and was valued at 5 shillings, or to return it to Pollard, believing it to be stolen. He told Pollard that he would get himself into “blue skin” over it. Pollard denied stealing the bird, claiming that he had found the goose dead at Cocking bridge.

[John Lithgow explained in court that he had served in the excise; and “blue skin” was a term used when an officer had a report made against him.]

On the following day, Wednesday, Benjamin Challen examined the bird and confirmed its identity, because of the speckled marks around its head.

At the Midhurst Petty Sessions hearing on 8th March in front of Richard Bingham Newland (the same magistrate as in the 1831 committal proceedings), Pollard again claimed that he had found the goose “dead by the bridge, rather nearer to Mr Rapley’s than to Mr Challen’s, on the night of Saturday, or it might be one or two o’clock Sunday morning last.” The magistrates were not convinced by this claim and committed him for trial.

At the Petworth quarter sessions on 6th April 1837, held in Petworth Town Hall William Pollard repeated his claim that he had found the bird at the bridge.

The chairman, summing up, observed that “when property which had been recently stolen, was found in the possession of a person, it was, unless very satisfactorily accounted for, a strong presumption of guilt”.

The jury, without hesitation, found Pollard guilty.

The chairman, in passing sentence, observed that the prisoner “had been in something like the same situation before, but had then saved himself by turning King’s evidence”. The sentence of the court was six months hard labour, with the last fourteen days in solitary confinement.

Henry Bulbeck and a loaf of bread

Of all the stories that I have come across in researching for this project, the punishment of Henry Bulbeck, a 29-year old married labourer with three children, seemed particularly harsh.

On the evening of Saturday 17th April 1841, Henry Bulbeck visited the shop premises of William Tupper at Cocking. While Mrs. Tupper was making up the order, her husband was in a side room when, through the doorway, he spotted Bulbeck take a pat of butter off the butter tub and put it in his pocket.

A few moments later, he returned to the shop and noticed a loaf of bread on the counter near where Bulbeck was standing. He continued to make up the order, but when he turned round again, Bulbeck and the loaf had gone.

Tupper and Mr. Challen, who was passing, followed Bulbeck and soon apprehended him. At first he denied any wrongdoing, but then brought the stolen items out from his pockets and said: “I am very sorry for what I have done. I hope you will forgive me.” When Tupper insisted that Bulbeck returned to the shop, he refused and ran off.

He was soon caught and taken back to the shop, where he offered to pay for the butter and loaf, but Tupper refused to accept it, even when Bulbeck offered him five shillings to let him go.

Instead, Bulbeck was handed into the custody of the village constable, who took him to Midhurst. He appeared in front of the magistrates two days later, when he was committed for trial at the next Quarter Sessions in Horsham.

At the July Quarter Sessions, Henry pleaded guilty to a charge of larceny, “stealing at the parish of Cocking, one loaf of bread, value 2d and one ounce of butter, value 1d.” He was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment with hard labour, with the last week of each month to be spent in solitary confinement.

Henry Bulbeck had married Eliza Luttman in 1834, and by the time of the court case they had three children, including two under two-years old.

The punishment meted out to Henry Bulbeck appears to be particularly severe. For the theft of 3 pence worth of food, for which he offered to pay, and pleaded guilty, he was sentenced to four months (17 weeks) hard labour. By way of comparison, in January 1836, William Underwood was sentenced to 10 weeks hard labour for stealing a pig valued at 10 shillings (40 times the value that Henry Bulbeck stole).

One other puzzle arises in this case: during the four months that Henry was incarcerated, how did Eliza maintain herself and her three young children? Presumably she was taken in by her parents, or threw herself on the mercy of the parish. It seems that the wife was punished just as hard as the culprit who was merely struggling to feed his family.

We’ve now covered roughly the first half of the century, so I’ll stop there for now. I will continue with the second half of the century in January, when you’ll hear about a marriage proposal in the courtroom, the brief crime wave following the arrival of the railway, the flashing vicar, the two friends who had an argument which ended in tragedy, and much more.