Part of the “Crime & Punishment in Cocking in the Nineteenth Century” series

The following talk was delivered at Cocking Village Hall on 23 January 2024. It is based on this series of articles, although there were occasional editorial amendments to make the talk more suitable for a general audience.

Talk (part 1) – 24 October 2023

Thankyou Andy for the introduction and for all the hard work you put into organising these talks. Thanks also to you all for turning out this evening.

Thankyou Andy for the introduction and for all the hard work you put into organising these talks. Thanks also to you all for turning out this evening.

In October, I presented my first talk which took us up to about the middle of the nineteenth century. Tonight, I will cover the second half of the century. Those of you who were here in October may recall that my main source for these stories was the various local newspapers available at the British Newspaper Archive.

The nature of crime changed gradually as the century progressed – there was a lot less theft of crops and livestock and, as conditions for the labouring classes improved slightly, an increase in crimes against the person, many fuelled by excess drinking.

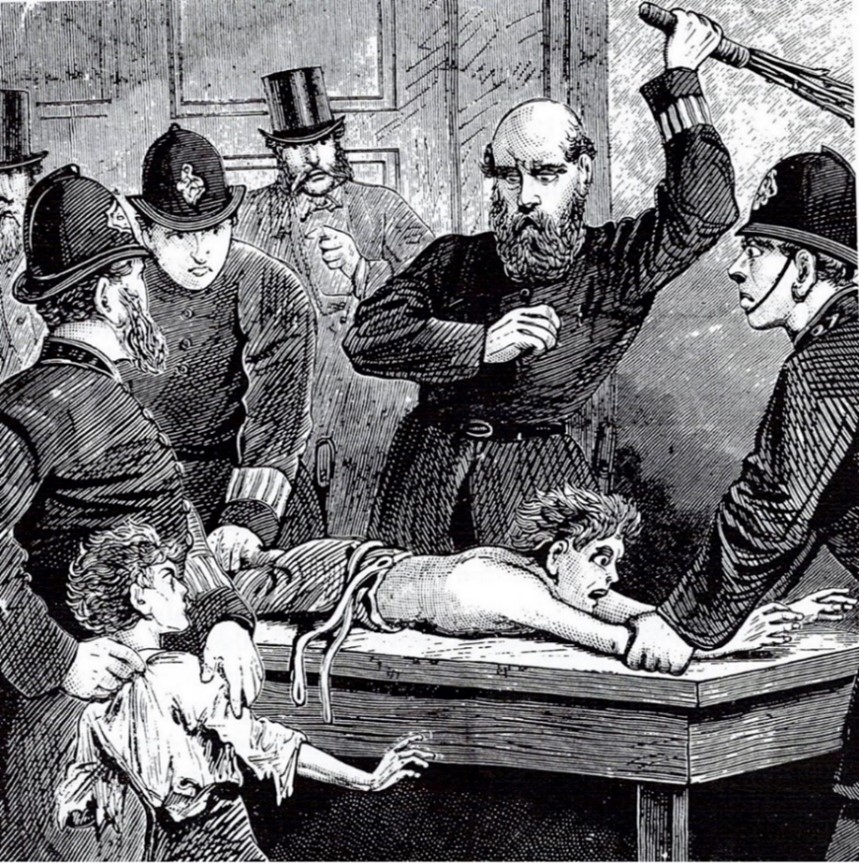

The Punishment of Children

During the nineteenth century, the punishment of children and young people who were in trouble with the law was particularly savage. It was only in the latter years of the century that the treatment of children began to show signs of improvement.

George Humphries

Stealing a length of chain

In February 1854, 10-year old George Humphries appeared before Midhurst magistrates, on a charge of stealing a length of iron chain, valued at 8 shillings.

On Monday 14 February, George had been seen by Police Sergeant Charles O’Neill dragging the chain along North Street in Midhurst. George took the chain to the blacksmith’s forge where he tried to sell it to Thomas Tribe, the blacksmith. When Mr Tribe asked George where he got the chain, George said: “I found it on the turnpike at Cocking Hill, about three or four months ago.” Tribe didn’t believe the story, so he put the chain around George’s neck and sent him away.

As he staggered under the weight, George was stopped by Sergeant O’Neill, who had been making enquiries around the town and had discovered that John Smart had lost a similar chain from his premises at The Wharf a few days earlier.

At the magistrates’ hearing, George was sentenced to six weeks hard labour and to be once privately flogged.

Charlotte Rogers

Theft of firewood

On New Year’s Day, 1856, 11-year old Charlotte Rogers, and her 8-year old sister, Jane were caught by Henry Farley stealing firewood from his farm at the foot of Cocking Hill. He testified that on coming down the hill, he saw two girls under his bavin stack. The elder girl was pulling logs from the stack and passing them to her sister. He went up to the two girls, when Charlotte came towards him with a bundle on her head. When the girls saw him, Jane dropped the bundle that she was carrying (which was wrapped in an old shawl) and tried to run off, but Mr Farley managed to detain them both. Charlotte claimed that her mother had sent them to the wood stack.

On New Year’s Day, 1856, 11-year old Charlotte Rogers, and her 8-year old sister, Jane were caught by Henry Farley stealing firewood from his farm at the foot of Cocking Hill. He testified that on coming down the hill, he saw two girls under his bavin stack. The elder girl was pulling logs from the stack and passing them to her sister. He went up to the two girls, when Charlotte came towards him with a bundle on her head. When the girls saw him, Jane dropped the bundle that she was carrying (which was wrapped in an old shawl) and tried to run off, but Mr Farley managed to detain them both. Charlotte claimed that her mother had sent them to the wood stack.

At the hearing in front of the Midhurst Magistrates, Charlotte was sentenced to 14 days imprisonment, while Jane was discharged. The magistrates “severely reprimanded” the girls’ mother, also called Charlotte, and “expressed their regret” that she couldn’t be indicted for receiving stolen property.

Elizabeth Payton

A little girl robbing an old woman

A little girl robbing an old woman

In May 1869, 11-year old Elizabeth Payton was a servant in the Cocking home of 81-year old Sarah Todman, the widow of a blacksmith. On 10 May, she was shaking up Mrs Todman’s bed and mattress when a bunch of keys dropped out. She picked up the keys and couldn’t resist the temptation to open the old lady’s moneybox, from which she removed a sovereign.

The theft was quickly discovered and the police were called; Elizabeth immediately confessed to the police.

At the magistrates’ hearing on 12 June she was committed to the West Sussex quarter sessions at Horsham. On the day of the magistrates’ hearing, Mrs Todman sat up in bed to ring for assistance, when she collapsed and died.

At the quarter sessions, Elizabeth pleaded guilty to theft. The court prosecutor said that “the girl had had a bad example set before her in some respects, and it was the wish of the prosecution that she should have the opportunity of amending her life, as she was so very young”.

Despite this plea, the court sentenced Elizabeth to three months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

Charles Whittington

Theft of a whip by a lad

We now jump forward 20 years to 1889, by when the treatment of children had improved following the passing of the First Offenders Act in 1887.

On the evening of 27 December 1889, 14-year old Charles Whittington was helping his brother-in-law, James Laker, stable horses at the premises of Henry Mills, a miller. Laker had laid down his whip on an oat chest by the stables, but the following morning, the whip was missing. He reported its disappearance to his employer, who called the police.

On the evening of 27 December 1889, 14-year old Charles Whittington was helping his brother-in-law, James Laker, stable horses at the premises of Henry Mills, a miller. Laker had laid down his whip on an oat chest by the stables, but the following morning, the whip was missing. He reported its disappearance to his employer, who called the police.

Three weeks later, on 23 January, PC Ellis visited Charles, who was then working at Cocking Causeway and found the missing whip. Initially, Charles claimed to have found the whip in Bex Lane, but eventually confessed to have taken it.

At the Magistrates’ hearing, he pleaded guilty to the theft of the whip, valued at 5 shillings. The magistrates made a “lengthy address to the prisoner” and gave him “a few words of good and sound advice”, but not wishing to send him to prison for a first offence, used the provisions of the First Offenders Act, and bound him over to be of good behaviour for six months, on a surety of £10.

Percy and Arthur Strotton

Apple stealers

In August 1891, Percy Strotton (aged 15) and his brother Arthur (aged 12) appeared before the Midhurst magistrates charged with stealing apples from the garden of William Ring-Smith, the village shopkeeper. They were charged with stealing 10 apples, valued at 2d, on 23 July.

In August 1891, Percy Strotton (aged 15) and his brother Arthur (aged 12) appeared before the Midhurst magistrates charged with stealing apples from the garden of William Ring-Smith, the village shopkeeper. They were charged with stealing 10 apples, valued at 2d, on 23 July.

During the hearing, the boys’ mother Elizabeth fainted; after she recovered, she explained to the court that her husband had left her, through jealousy the previous week.

The boys were given “a good talking to” by the bench, and bound over to be on good behaviour for six months.

Elizabeth Strotton

A serious charge of rape on a married woman

Some of the people involved in these cases appeared on court on another occasions. Thus, I mentioned Elizabeth Strotton earlier, when she fainted at the trial of her sons in 1891.

25 years earlier, she had appeared at the Spring Assizes in Lewes when she charged Edward Savage with rape.

On 1 February 1866, she was at her home in Bell Lane when Edward Savage, a hawker, arrived at her door and tried to sell her some blankets. She said that she had no money and told him to go away. He then went to his cart and came back with some cloth which he offered her for 3s 6d. She once again stated that she had no money, when he took hold of her and kissed her, asking her to kiss him back, which she refused. He then locked the door and threw her to the ground and raped her. She passed out and when she came round, Savage had left.

In Savage’s evidence, he claimed that she agreed to exchange the cloth for “sexual favours” and that she “was quite agreeable to his proposals”.

At the trial, the defence lawyer suggested that Elizabeth was a woman of loose morals, and that she was “immodest and unchaste” and was a willing party.

The jury were unable to reach a verdict in view of the conflicting claims of Elizabeth and her assailant, and the case was dismissed.

Charlotte Rogers and Mark Marshall

Popping the question in public

You may also recall that in 1856, 11-year old Charlotte Rogers was sentenced to 14 days imprisonment for stealing firewood.

Seven years later, she was back at Midhurst Magistrates court on 9 April 1863. Now aged 18, she was claiming financial support from 25-year old Mark Marshall – her son William had been born the previous October.

My grandchildren, Kitty and Noah, have agreed to help me enact the court hearing:

Magistrate to Charlotte: Has the father of the child given you any money?

Charlotte: Yes, sir. But only a shilling or two.

Magistrate to Mark: Do you agree that you are the father of the child?

Mark: Yes, sir.

Magistrate: Why have you not paid what you agreed?

Mark: I dunno. I’ve got no money. But I’ll have the gal, gentlemen. I want to know if she’ll have me.

Magistrate: That’s not a matter for this court. You must discuss that in private.

Mark (turning to Charlotte): Will you be wed?

Charlotte (smiling): Yes!

Mark (to the bench): I must keep a wife someday, gentlemen, I suppose.

Magistrate: Thank you, Mr Marshall. The order of this court is that you pay Miss Rogers one shilling a week. You can, of course, marry the young lady if you like.

Sadly, this story does not have a happy ending. The couple never married and poor Charlotte died from typhoid at Easebourne Workhouse in April 1866, still only 21 years old. Her son, William, was brought up by his grandmother and his aunt, Jane.

Joseph Clarke

Arson with intent to be transported

On 28 October 1861, Joseph Clarke a 19-year old out of work bookbinder attempted to break into some cottages at Singleton, before coming to Cocking, where he set fire to a haystack, the property of Edward Hopkins, the licensee of the Blue Bell inn. Clarke immediately gave himself up to the police and was taken into custody and committed to trial at the next assizes.

On 28 October 1861, Joseph Clarke a 19-year old out of work bookbinder attempted to break into some cottages at Singleton, before coming to Cocking, where he set fire to a haystack, the property of Edward Hopkins, the licensee of the Blue Bell inn. Clarke immediately gave himself up to the police and was taken into custody and committed to trial at the next assizes.

In March 1862, Clarke appeared in court at Lewes where he pleaded guilty to a charge of arson, and other offences. In sentencing Clarke, the judge said that he had no doubt that Clarke had committed the act thinking to get transported. In this, he would be disappointed; transportation was now in a great measure done away with, and he would sentence him to “Six Years Penal Servitude”.

Police Constable Richard Denman

In 1864, Cocking had a new resident Police Constable, 25-year old Richard Denman. During his spell at Cocking police house, the reported crime rate increased significantly, with 18 cases reported in seven years. As a result of his zeal, anyone allowing their cattle to roam on the highway found themselves in front of the magistrates, but most of the cases involved drunken behaviour.

Joseph Mitchell

Far too fast at Cocking

Early in the morning of Friday 4 November 1864, PC Denman noticed two carts parked rather haphazardly in front of the Blue Bell inn. At about 4 o’clock that afternoon, he came across them again, now seemingly abandoned by the church gate, blocking the lane to Heyshott.

He went up the lane to the pub, where he found the owner of the carts, Joseph Mitchell, who was by now “very drunk”. PC Denman asked Mitchell to move his carts or be arrested.

Mitchell replied “Who the ____ cares for you? Move them yourself if you wants to move them, for I won’t!”

Having gone on his rounds, later that evening, PC Denman returned to find that the carts had been moved onto the turnpike road. He again asked Mitchell to leave the village, but Mitchell refused and after a long argument during which Mitchell “swore a great deal”, he laid down in the middle of the road, and refused to move.

Mitchell was then arrested and spent the night at Midhurst police station, before appearing the following day at Midhurst magistrates. He pleaded guilty to a charge of drunken behaviour, saying “I’m very sorry for it. Don’t know what I do when I gets a little beer.” He was committed to jail for seven days.

Mitchell was back in court 11 years later, on 18 May 1875, when he and his wife, Jemima, had been causing a disturbance at the Blue Bell. After they left the pub, they made their way with their wagon through Bepton and on to Didling, where they broke open a gate. PC Walter Duffield had followed the family from Cocking, and tried to arrest Joseph Mitchell, who responded “I won’t be taken by any man. I’ll split your ___ head open.” After a brawl, Mitchell was eventually handcuffed and taken to Midhurst police station. The next day, he was fined £2 12 shillings for assault on a police officer.

During the brawl, PC Duffield was assisted by Thomas Woolford, who lived nearby. As he was pulling Mitchell away, Jemima Mitchell came at Woolford with a crowbar and lashed out, shouting “I’ll split your ___ skull if you don’t let go of my husband”. She continued to attempt to hit Woolford several times as the party made their way to Midhurst, before her teenage son, also called Joseph, joined in, saying to his father: “Don’t walk. Kick him in the shins”, before turning on Woolford: “You white-slopped bastard! I’ll split your skull with a hammer for hitting my mother”, before hitting Woolford on the arm.

Jemima and Jospeh Mitchell junior were both fined for assault on Thomas Woolford, and fined 15 shillings and 12 shillings respectively.

Mary Ann Dudman

Summonsing a Police Constable – A laughable case

On 1 December 1864, the tables were turned when PC Richard Denman appeared in front of Midhurst Magistrates, on a charge of assault brought by 64-year old Mary Ann Dudman. From the press reports, it would seem that Mary Ann was a very large lady, while her husband, 73-year old Thomas, was small and rather timid.

Shortly before 8 o’clock in the morning of 5 October 1864, Mary Ann had left her cottage at the corner of Crypt Lane to walk to Crypt Farm to buy some milk. She had not gone far when she started to feel sick so she sat on the bank on the edge of the lane.

According to her evidence to the court:

I was very unwell, and sat down on the bank in the lane; this was about half past eight o’clock in the morning. About nine o’clock, the policeman came along, pulled me up on the road, and then threw me down again, telling me to go home. Before he touched me, he said: “What are you doing here? Go along home.” I said, “I shan’t go home. I’ve as much right here as you have, and here I shall stay, for you or anybody else.” He then took hold of me, threw me down in the road, and dragged me along about 20 yards. He threw me down three times. I have now bruises on both of my hips where he took hold of me.

He hurt me very much. This lasted quite two hours; and all this time, he was trying to take me home. There were several there by this time; amongst them my husband, who asked him to take me home on his back.

PC Denman’s version of the events was somewhat different:

At about eight o’clock, Mr Dudman came to me, and in consequence of what he said, I went about 10 o’clock, or soon after, up Crypt-lane. I saw the woman laying in a dry ditch by the road side; she had a cloak partly over her head, there were several there at the time. Mrs. Lambert and others, who saw all that took place. When I got there, I asked her to get up and go home. She said she was so weak and ill she couldn’t walk if she got up. I lifted her up and tried to assist her along, but she wouldn’t stand, and rolled over into the middle of the road. I put her on her feet again, but it was no use. She rolled along the middle of the road several yards. Three times I stood her up, but finding it was no use, I left her there; the husband was there all the time.

Mary Ann then interrupted: “That’s according to your idea.”

She then turned on her husband: “Did you tell the constable to fetch me home?” After a little hesitation, he admitted he had. “Why hadn’t you owned it before?”

After the magistrates dismissed the case, Mary Ann continued to berate her husband as they left the court house.

James Chivers and James Boxall

Nocturnal disturbances at Cocking

At about 12:30 early in the morning of Saturday 20 July 1867, PC Denman was on duty in Cocking, when several men came out of the Blue Bell inn “in a state of intoxication”, creating a public disturbance, including James Chivers and James Boxall.

PC Denman suggested that Chivers go home quietly, but he refused and started using foul and abusive language. Denman said that he would take Chivers into custody if he did not desist, but Chivers became more belligerent, saying “Have you ever seen me before?” Denman said that he had and that he knew who he (Chivers) was and repeated the threat of arrest. Chivers then challenged Denman to “fight it out”.

PC Denman then tried to arrest Chivers but before he could restrain him, Chivers ran off, but was soon captured and taken to Midhurst police station along with James Boxall.

At the next magistrates hearing, both men were fined 5 shillings.

Benjamin Shotter Challen

One to be pitied

In the first half of this talk, there were frequent mentions of Benjamin Challen, who was the victim of several thefts of crops and livestock from his farm at Brook House. His oldest son, Benjamin Shotter Challen was born at the farm in December 1826. By the time he was 24, he was living at Manor Farm, Didling with 1200 acres, employing 45 men and 16 boys. His housekeeper had a 16-year old daughter, Sarah Ann Elliott. Benjamin and Sarah ended up together and their first child was born in 1860. Although they were not legally married, Sarah Ann took the surname Challen and the couple acted as man and wife.

The relationship caused a family rift and Benjamin was “disowned” by his parents and excluded from his father’s will. By 1865, he had left Didling and was living at Tillington, where he and Sarah Ann had two further children.

On Thursday 10 October 1867 – described as a “well-built man, with disordered flaxen hair and sandy whiskers” – Benjamin was brought up before the Mayor of Godalming, on a charge of wandering about that town, with no visible means of subsistence.

PC Franks testified that earlier that morning, at about 1 o’clock, he had found Benjamin leaning against the window sill of a shop in the High Street. As he could not give a satisfactory account of himself, he was taken into custody.

At the Police Station, Benjamin said that he had walked from Cocking (some 20 miles – at least a 7 hour walk) the day before and had tried to find a room at The Angel Hotel in the High Street, but had been refused as he had no money on him. When asked by the mayor how he expected to pay for his bed if he had no money, he replied “I’m like Royalty, I suppose.”

The report in the Chichester Express suggests that his behaviour “excited the impression that he was an imbecile [who] had wandered from the custody of his friends” despite appearing “to belong to a superior class of society”. According to Constable Burt, “the man had such delicate hands and spoke so well, that he [gave the impression] that he had been a policeman.”

The mayor sentenced him to be remanded in police custody until the Saturday.

In August 1871, Benjamin and Sarah Ann emigrated to the United States, where they had two further children. On 26 February 1880, the couple were finally married at Niagara Falls.

After the death of Sarah Ann, Benjamin returned to Cocking, where he died in January 1894.

Even in death, he was not re-united with his parents – his grave is about six feet from that of his mother and father in Cocking churchyard.

Even in death, he was not re-united with his parents – his grave is about six feet from that of his mother and father in Cocking churchyard.

John Lee

An obstructionist on the road

On Saturday, 30 June 1877, Lord and Lady Leconfield, accompanied by their agent, Robert Downing, were in their trap with Lady Leconfield driving, making their way between Singleton and Petworth. Just after passing Drove House, they came up behind a horse and cart under the control of John Lee, who was asleep with the reins dragging along the ground.

On Saturday, 30 June 1877, Lord and Lady Leconfield, accompanied by their agent, Robert Downing, were in their trap with Lady Leconfield driving, making their way between Singleton and Petworth. Just after passing Drove House, they came up behind a horse and cart under the control of John Lee, who was asleep with the reins dragging along the ground.

They called out as they went past, which woke up Lee, who took hold of the reins of his cart, swearing loudly as he did so. A few minutes later, Lee had whipped his horse and managed to pass the Leconfields’ trap, before he slowed down to walking speed. Downing then took the reins and drove past Lee, who again put his horse into a gallop. Lee drove down Cocking Hill “as fast as he could go” and continued at full speed through Cocking and on to Cocking Causeway. Here, Lee continued to Midhurst, while the Leconfield trap turned off to take the Petworth road.

They called out as they went past, which woke up Lee, who took hold of the reins of his cart, swearing loudly as he did so. A few minutes later, Lee had whipped his horse and managed to pass the Leconfields’ trap, before he slowed down to walking speed. Downing then took the reins and drove past Lee, who again put his horse into a gallop. Lee drove down Cocking Hill “as fast as he could go” and continued at full speed through Cocking and on to Cocking Causeway. Here, Lee continued to Midhurst, while the Leconfield trap turned off to take the Petworth road.

At the Petty Sessions held at Petworth on 15 July, Robert Downing testified that he had not the slightest doubt that John Lee was drunk at the time of the events. The defendant called Henry Knappet, the landlord of the Horse & Groom at West Ashling, who testified that John Lee was “perfectly sober when he came to [his] house and also when he left”, but on cross-examination it transpired that the witness was speaking about a different occasion.

The magistrates stated that Lee had “run the imminent risk of being placed in the dock on a more serious charge”, but found him guilty of “being drunk while in charge of a horse and cart”, describing this as a “most serious offence”, as his conduct might have caused an accident.

Lee was fined 10 shillings plus 15s costs, or 14 days’ hard labour for failure to pay.

The Killing of George Marshall

Suspected murder at Midhurst

At about 6 o’clock on Saturday, 22 January 1876, 19-year old George Marshall and 27-year old Thomas Woolford caught the omnibus from Cocking to Midhurst.

After passing the Royal Oak inn, and starting the final descent into Midhurst, the omnibus “broke down” and was unable to complete the journey. The two men helped detach the horses from the omnibus, and led them to the bus depot in Petersfield Road.

After leaving the horses at the depot, the two men went to the Omnibus & Horses beerhouse next door, where they were joined by Thomas’s brother James in the smoking room. Later in the evening, the three men had an argument about money that Thomas owed his father. The argument became rather heated, when the landlady, Mrs. Emily Puttick, advised them to be quiet and not to make a disturbance.

After leaving the horses at the depot, the two men went to the Omnibus & Horses beerhouse next door, where they were joined by Thomas’s brother James in the smoking room. Later in the evening, the three men had an argument about money that Thomas owed his father. The argument became rather heated, when the landlady, Mrs. Emily Puttick, advised them to be quiet and not to make a disturbance.

Shortly after, James left saying that his brother was being “disagreeable”. Another customer, Benjamin Dabbs, left the bar at about 9:30; as Dabbs made his way out, Thomas came to the bar door and said, “I’m going to have a ____ go at him, presently.”

Thomas Woolford and George Marshall left the beerhouse together at about 10:00; neither man was drunk, and both appeared to be quite amicable.

After passing the Spread Eagle, the two men made their way up Chichester Hill. At about 10:30, Sarah Burt heard two men having an argument as they passed her cottage going towards Cocking. She heard one man say, “Just as you like”, to which the other replied “Come on up here”. The voices then passed on before, a few minutes later, she heard shouting from about 60 yards up the hill, before it went quiet.

Thomas Woolford arrived at his lodgings in Cocking at about 11:45. His landlady, Harriet Burrows asked him where he had been and why he was so late coming home. Woolford replied that he been into Midhurst drinking with George Marshall who he had last seen following him up Chichester Hill.

At about 11:00, a group of men were making their way home towards Cocking, when one of them, James Tribe, stumbled across a body lying partly in the ditch on the side of Chichester Hill. He called his companions, and they soon realised that the man was dead. The police were called and were quickly in attendance, and moved the body into the road to examine it, when one of the men identified the corpse as that of George Marshall. A doctor was then called, who confirmed that the man was dead, before the body was carried to the Spread Eagle, about 400 yards from where the body was found.

Several of the men then visited the home of George Marshall and told his family about his death, before going to Thomas Woolford’s lodgings, where they arrived at about 12:30 on Sunday morning. Woolford was asleep and refused to get up. Early next morning, Mrs. Burrows challenged Woolford who again refused to talk about what had happened, before the police arrived to take him into custody.

At the inquest the following week, the coroner heard evidence from Dr Robert Orme with the findings of his post mortem, which revealed multiple scratches and bruises , especially on the cheek, as if from a punch, and around the neck. A bone in the trachea, directly under the bruises on the right of the neck, was broken, probably caused by a thumb pressing hard. His opinion was that death was caused by strangulation.

Harriet Borrows, Woolford’s landlady, described the state of Woolford’s clothes on the Sunday morning, which were bedaubed with mud; the knees of the trousers were wet, as if he had been saying his prayers.

Two hats were then produced as evidence, one of which was found on the road near the body and the other in Woolford’s room. George Marshall’s sisters examined the hats and declared that the hat found in Woolford’s room belonged to their brother, being newer and less scruffy than the one found in the road.

Two hats were then produced as evidence, one of which was found on the road near the body and the other in Woolford’s room. George Marshall’s sisters examined the hats and declared that the hat found in Woolford’s room belonged to their brother, being newer and less scruffy than the one found in the road.

Thomas Woolford was committed for trial at the Spring Assizes at Lewes on 11 March 1876, before Sir Anthony Cleasby, on a charge of wilful murder. At the end of the hearing, the judge addressed the jury, explaining the difference between murder and manslaughter at considerable length.

After a brief discussion, the jury found Thomas Woolford guilty of manslaughter.

The judge then discussed the question of sentence. Addressing the accused, he said,

“… in using the violence you did, you ran a great risk of losing your [own] life, for I am not at all sure that, on a stern administration of the law, it might not be deemed a case of murder. It is a humane verdict, and I think a proper one, which reduces the offence to manslaughter.

But still, although only manslaughter, it must be punished as a very bad case of manslaughter, for although there was not that malignant intention which would have made it murder, deadly violence was used in the course of the struggle. The practice of using this sort of savage, deadly violence is a disgrace to this country, and it is the duty of Judges to endeavour to put a stop to it, by making severe examples in cases where the circumstances appear to justify it.

…the sentence upon you is that you be kept in penal servitude for 15 years.”

The Railway Comes to Cocking

The brief episode of navvies vs local residents

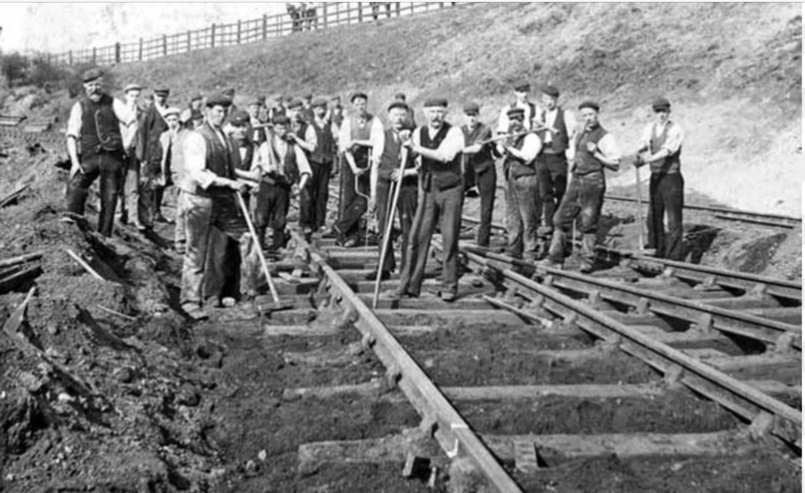

After a false start in the late 1860s, the construction of the Chichester to Midhurst branch of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway began in earnest in January 1879. The works involved the digging of a 740 yard tunnel under Cocking Hill and other major earthworks.

After a false start in the late 1860s, the construction of the Chichester to Midhurst branch of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway began in earnest in January 1879. The works involved the digging of a 740 yard tunnel under Cocking Hill and other major earthworks.

As a consequence, there was an influx of navvies and other railway staff into the village, and the construction of a temporary worksite with huts to accommodate the men. The population of Cocking village increased by over a quarter: at the 1881 census, there were 60 men engaged on the railway, together with their wives and children, another 49 living in the camp or lodging in the village. The influx of so many men into the village caused friction with the local population, and there were several incidents of violence involving the railwaymen.

George Gorden

Shameful outrage at West Lavington

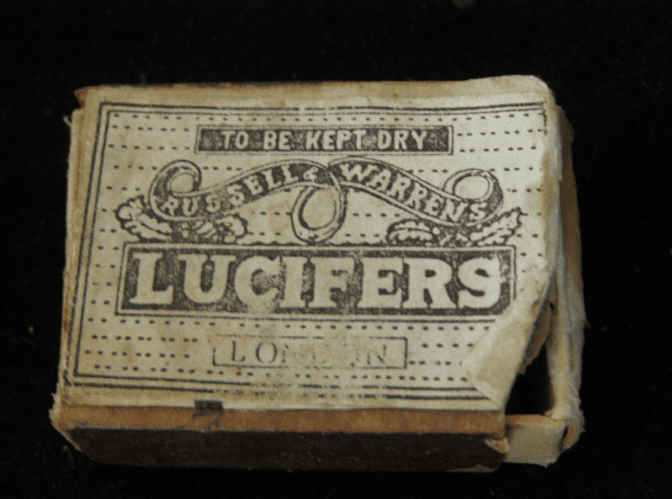

The first recorded incident involving a navvy came on 27 May 1879, when 11-year old George Murrant had been sent by his father from their home at Todham (between West Lavington and South Ambersham) to purchase some Lucifer matches in Midhurst.

The first recorded incident involving a navvy came on 27 May 1879, when 11-year old George Murrant had been sent by his father from their home at Todham (between West Lavington and South Ambersham) to purchase some Lucifer matches in Midhurst.

On his return via King John’s Walk, he was stopped by George Gorden, who knocked the younger George to the ground and stole the matches (value 1½ pence). Gorden then cut open George’s pockets with a knife, before tying George’s hands behind his back, and running off.

Poor little George was able to walk home (about ¾ mile) but couldn’t get into the house, as his hands were still tied. Eventually, he managed to raise his father who came to the gate and cut him free.

Gorden had been seen loitering in the area on several previous days, and was soon arrested at Cocking railway works. At the Midhurst Magistrates hearing on 29 May, Gorden pleaded guilty to charges of assault and robbery and was committed to two months hard labour.

George Taylor

Brutal attack on keepers at Cocking

At about midday on Tuesday 14 October 1879, James Blunden and Henry Denman, gamekeepers to Lord Egmont, were on the west side of Cocking Hill when they spotted two men coming up from the neighbouring field near Crypt Farm from the direction of the railway huts; the men were accompanied by a large black dog and carried nets and bludgeons. They then joined another three men with another dog, who were kneeling down under a yew tree, with nets over a rabbit hole. The gamekeepers challenged the men and asked what they were up to. “Netting a bit”, came the response “but we didn’t get much sport”. As Blunden blew his whistle, the men ran off, with the two ‘keepers in pursuit.

As they caught up with the men, Denman tried to grab a bag off one man’s back, but he turned and struck Denman across the head with his stick. As the poacher was about to strike a second blow, James Blunden jumped between them and knocked the stick away. Another man then struck Blunden a blow on the head knocking him down. As he looked up, James Blunden saw the man was about to hit him again, and tried to turn away, but was struck again, firstly on his arm by the bludgeon and then on the head with a large rock, which broke the ridge of his nose, leaving him unconscious, as the poachers made their escape.

Denman followed the men down the lane; they turned several times to throw stones at him, and threatened to “knock his brains out”.

By now, P.C. Alfred Hawkins had been called and saw the men hiding in a copse; when he tried to question them, they said, “Come any closer, and we’ll murder you.” He ordered them to come quietly, to which they raised their sticks, saying, “We’ll settle you if you come any closer”. P.C. Hawkins then blew his whistle, and took hold of one of the men, George Taylor. Taylor, described as a “miner”, and his dog were taken to Cocking police house, but the other poachers escaped.

In the meantime, James Blunden was taken to Midhurst where he was attended to by Dr. Joseph Stenson Hooker. His injuries included two large, lacerated wounds on the scalp, through which the bone was visible, a broken nose, a sprained wrist and severe bruising between the shoulder and elbow, with a large loss of blood. He was unable to return to his duties for two months after the beating.

At the Sussex Winter Assizes held at Lewes on Monday 19 January, Taylor was found guilty of unlawful wounding. The judge criticised the cruel and cowardly way that Taylor and the other men had beaten James Blunden with sticks and stones. In the circumstances, he could not do less than sentence Taylor to twelve months’ hard labour.

Teddy O’Neil

Savage assault on a police constable

Late in the evening of Saturday 10 April 1880, P.C. Edward Churcher was on duty near the Cobden Arms when he saw a group of navvies quarrelling and “making use of filthy language”. He approached them intending to advise them to stop the noise and go home, but before he could get past “I advise you chaps …”, they turned on him. One of the group kicked him in the back, sending him to the ground, when another man (later identified as Teddy O’Neil) jumped onto his stomach, while the others kicked him several times in the ribs. O’Neil said, “I promised this a long time ago, you bastard, and now we’ll do for you.”

Churcher was kicked again and kneed in the stomach by O’Neil. He pleaded for them to stop: “For Good Luck’s state, give a fellow a chance.” He was again hit in the face by O’Neil, who said, “Will you let us go free, if we leave you alone?” Churcher replied, “It strikes me that I shan’t be able to move far”. O’Neil released the constable, who still had sufficient presence of mind to draw his truncheon and strike O’Neil on the head.

O’Neil yelled out, “Murder!” as his companions ran off. The two men tussled on the ground when O’Neil bit Churcher on the right hand. Churcher responded by hitting O’Neil with his left hand, managing at the same time to get one handcuff on to O’Neil.

By this time, a large group had formed including retired constable, Frederick Marshall, who helped Churcher manhandle O’Neil into a van and take him to Midhurst police station. In the van, O’Neil continued to threaten and lash out at both Churcher and Marshall, kicking Churcher in the face and “rendering [him] insensible”. When O’Neil’s boots were removed at the police station, they were found to be full of blood.

Churcher had part of his whiskers ripped out during the mêlée and his injuries prevented him from returning to duty, although there were no internal injuries. He had severe bruising about the face, especially the right eye, there were bite marks on his hand and his ribs and shins were bruised.

At the Midsummer Sessions held at Horsham on 1 July 1880, O’Neil claimed to be “quite drunk”; he could recall nothing of the incident.

After the jury had found O’Neil guilty of assault, the judge thanked P.C. Churcher for his remarkable behaviour during the assault, and recommended him for a suitable honour from his Chief Constable. He told the prisoners that he had never come across a more serious case of assault on a uniformed police officer during the performance of his duties. The attack was “most un-English and cowardly”, while the constable had “behaved like an Englishman and tried to do his duty”.

O’Neil was sentenced to 18 month’s hard labour.

Thwaite George Tomlinson

A serious charge against a clergyman

On Tuesday 3 August 1889, 54-year old Revd. Other Crimes of a Sexual NatureThwaite George Tomlinson appeared before the Midhurst magistrates on a charge of Indecent Exposure.

Tomlinson had been officiating at West Lavington church in the absence of the vicar, Thomas Wainwright, who was away on holiday. He was accused of exposing himself to three young girls at Cocking Causeway, and was found guilty. He was fined £20 with costs of £2 8s 6d, with the alternative of two months’ imprisonment with hard labour if he failed to pay.

Thwaite George Tomlinson was the son of a vicar and was ordained as a deacon in 1860, following which he served as a curate in various parishes in the Midlands. In 1885, he was ordained as a priest at Lichfield, and took up the post as vicar of the tiny parish of Cautley in north-west Yorkshire.

Despite the incident at Cocking, he continued in the priesthood firstly in East Anglia. but by 1903, he was curate at Brailsford, in Derbyshire. On 8 October 1903, he appeared at Ashbourne police court on a charge of indecent exposure to three boys and was committed for trial at the forthcoming Derbyshire assizes.

The original hearing at the assizes was adjourned as Tomlinson was unfit to plead, and on 6 November, he was admitted to Mavisbank Asylum near Edinburgh. At the adjourned hearing on 2 December, the medical superintendent of the asylum, Dr Wilson, confirmed that Tomlinson has been admitted as a lunatic and was “hopelessly insane”, and was incapable of understanding the charges against him. Dr Wilson stated that, in his opinion, Tomlinson had been “of weak mind” for many years. As a result, the judge adjourned the trial sine die.

Despite the medical opinion, Tomlinson was discharged the following February. It would appear that he spent the rest of his life in and out of institutions.

He was arrested again in April 1907, shortly after being released for the third time from an asylum, when he committed a similar offence to the previous two, at Gestlingthorpe in Suffolk. At the assizes on 21 May, he was again reported to be unfit to stand trial and unable to understand the nature of the charges against him. His lawyer said that Tomlinson should be returned to an asylum but had insufficient income. He was very deaf, and had very few friends or living relatives. Revd. T.P Worrall, rector of Beesby, in Lincolnshire was a relative by marriage and was prepared to take Tomlinson in and find him a safe home.

Again, the case against Tomlinson was adjourned sine die and he was discharged into the care of Revd. Worrall.

Tomlinson died, aged 79, at Isleworth Union Infirmary near Brentford, Middlesex on 12 March 1914.

John Williams

A three-fold charge

On the night of Thursday 16 May 1895, James Lee, a pedlar, and 16-year old John Williams had both been staying at the Coach & Horses in St Pancras, Chichester. When James Lee woke next morning, he discovered that all his stock [19 pairs of spectacles, one spectacle case, eight rings and two combs] had been stolen.

By this time, John Williams had made his way nine miles north to Cocking, where he met 5-year old John Tier and 6-year old Albert Batten, who were on their way to school from their homes at Cocking Causeway. He demanded that the boys empty their pockets, and made off with John’s clasp knife and Albert’s lunch [three slices of bread and butter, three slices of bread and jam and one egg].

Later that day, John Williams was arrested in Midhurst by PC Ward who found the items from James Lee and John Tier still in his possession. (Presumably he had eaten Albert’s lunch!) He was brought before the magistrates the following week, where he was committed for trial at the next Quarter Sessions.

James Lee, the pedlar, pleaded with the magistrates for the return of his goods, but these were required as evidence. Without his stock, he was destitute and unable to earn a living. The magistrates took pity on him, and gave him 10 shillings, with the clerk adding 2s 6d and another person in the court gave him a further shilling, to tide him over until his stock could be returned after the Assizes.

At the Quarter Sessions held at Horsham Town Hall on 20 June, John Williams pleaded guilty to all three charges (total value £1, 9 shillings & 5 pence) and was sentenced to six months hard labour.

Thank you again for coming this evening, and to Noah & Kitty for their performance as Mark Marshall and Charlotte Rogers.

My special thanks, however, must go to all your ancestors and the former residents of this law-abiding village for providing me with such a rich choice of stories to tell you over these two evenings.

All these stories and several others are featured in more detail on my website at www.sussexpeople.co.uk/crime.